11 Feb Ancestors-Newsletter- February 10, 2024

Contents

- 1 ANCESTORS- DURING WWI, A GERMAN OFFICER TRIES TO BLOW UP A BRIDGE AT THE U.S.-CANADIAN BORDER AND IS SENTENCED TO ONLY 30 DAYS IN JAIL

- 2 EARLY SURRY VIRGINIA- FARRAR, JORDAN, PERRIN, ROYALL AND RANDOLPH TO THE FOUNDING FATHERS, JEFFERSON AND MARSHALL

- 3 ROARING GIRL, LONDON’S SHARP-ELBOWED LOUDMOUTHED MARY FRITH

- 4 WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

ANCESTORS- DURING WWI, A GERMAN OFFICER TRIES TO BLOW UP A BRIDGE AT THE U.S.-CANADIAN BORDER AND IS SENTENCED TO ONLY 30 DAYS IN JAIL

ANCESTORS- DURING WWI, A GERMAN OFFICER TRIES TO BLOW UP A BRIDGE AT THE U.S.-CANADIAN BORDER AND IS SENTENCED TO ONLY 30 DAYS IN JAIL

Ancestors ask about the railroad bridge over the St Croix River between Vanceboro, Maine and McAdam, New Brunswick, was an essential link on the Grand Trunk railroad, which fed war materials from Canada and the United States to the port of St. John, New Brunswick. The bridge had been unguarded on the night of the attempt, even though experts say the destruction of the bridge would have seriously reduced the usefulness of the Port of St. John. This port was crucial to supplying Allied armies in Europe. The Germans realized this if the U.S. and Canadian authorities did not.

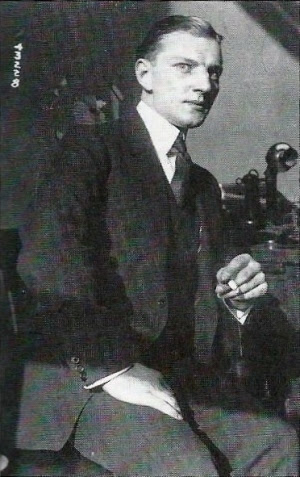

Lt. Werner Horn, shown above, was an interesting fellow. About 33 years of age, he was patriotic, brave, and surprisingly compassionate. He was not, however, according to those who subsequently interrogated him, overly bright or trained in demolition. He had been in the German Army for ten years before being inactivated, after which he moved to Guatemala in 1911 to manage a coffee plantation. He was reactivated when war between England and Germany was declared in August of 1914, and, obeying a general command from the German Army, he tried unsuccessfully to return to Germany. He eventually reported to the German Consulate in New York, where the German military attaché in the U.S., Captain Franz van Papen, contacted him. Van Papen and his associates had orders from Berlin to arrange acts of sabotage within the U.S. to disrupt the Allied war effort in Europe, and Lt. Horn fit perfectly into their plans. Lt. Horn could move freely because the United States was still neutral in 1915.

In New York, Horn was given a suitcase of dynamite, a railroad map of eastern Maine, and a ticket to Vanceboro, ME, where he arrived on January 30, 1915. He checked into the Vanceboro Exchange Hotel run by Mr. Aubrey Tague, but not before arousing the suspicion in the entire town and establishing beyond doubt his unfitness as a secret agent. Upon alighting from the train, he was seen hiding his suitcase in a woodpile, from which he walked to the railroad bridge and conducted a very discreet surveillance.

Only after this did he retrieve his suitcase from the woodpile near the Vanceboro Railroad Station and check into the hotel, where he was being tipped off to his activities. Horn was soon interrogated by the chief U.S. customs officer in Vanceboro. He told the official he was a Dutchman looking to buy a farm in the area. Since the customs officer established Horn had not entered the country illegally, he decided he had “no jurisdiction” and dropped the matter.

Horn remained rather inconspicuous for the next day and checked out of the hotel on the evening of February 1, 1915, telling Mr. Tague, the owner, that he was going to take the 8 o’clock train. He hid in the woods until midnight, but as the temperature that night was 30 below with a strong wind, he must have already been nearly frozen when, just after midnight, he started across the Vanceboro railroad bridge to the Canadian side at McAdam. Some reports claim he changed while waiting into his German army uniform to preclude any claim he was a spy for which hanging was the punishment. However, this is unlikely. He waited until midnight because he had agreed to destroy the bridge only on the condition that no one would come to harm, and van Papen had assured him no trains used the bridge from midnight to early morning. Halfway across the bridge, he was surprised to hear a train whistle and, finding himself face to face with an oncoming train from the Canadian side, he leaped over the side and held onto the bridge supports until the train passed. This disconcerted him, but he soldiered on, frozen and surely scared, only to hear a whistle behind him. Again, he found himself in the path of a train from the U.S. side, from which he barely escaped. He now realized van Papen’s information about the Vanceboro train schedule was incorrect or, more likely, a fabrication. This resulted in a change in Horn’s plans.

In addition to the 60 lbs of dynamite, Lt. Horn had a 50-minute fuse. The 50-minute fuse was intended to allow Horn enough time to escape Vanceboro before the explosion. Horn intended to light the fuse and walk through the night the short distance, or so it appeared on his railroad map, to Princeton to catch the morning train and effect his escape. Horn did not understand the Maine woods, especially at 30 below zero in winter. He almost certainly would have frozen to death. However, he now had to change his plans to avoid any possibility of the loss of human life, and this involved risking his own and almost certainly conceding his capture. He cut the fuse to 3 minutes, placed the charge under a bridge support on the Canadian side, and listened carefully to ensure no trains were coming. He lit the fuse and barely got back across the bridge before a huge explosion woke up the entire citizenry of the two towns. Fortunately for the war effort, the explosion only slightly damaged the bridge. As Horn was later to concede, he did an inferior job of it because his hand and feet were frozen.

At about 2 A.M., Mr. Tague was checking the boiler at the hotel, thinking it may have been the source of the explosion that had shaken his hotel, when he heard the hot water running in the bathroom. Surprisingly, he found Werner Horn, who had checked out only a few hours earlier, running hot water over his hands. “I freeze my hands”, he explained. Tague opened the window, handed Horn some snow, and suggested rubbing this on his hands. Horn asked for a room, which Tague provided, and went to bed. The cause of the explosion was quickly determined, and the investigation just as promptly led the authorities to Horn. Well, perhaps not all of the authorities

About 7 in the morning a posse of officials led by the Superintendent of the Maine Central Railroad knocked on Horn’s hotel door and demanded he open it. He obliged, and Lt. Horn was arrested with no resistance. He readily admitted he was responsible for the attempt to blow up the bridge but claimed he was legally not only justified but required as an officer in the German Army to attack the enemy. He rightly pointed out his action was carried out in enemy territory, Canada, where a state of war existed with his country, Germany. U.S. authorities were perplexed and uncertain about Horn’s legal status. The Canadians and English demanded his immediate extradition for trial or, given the outrage in New Brunswick, lynching.

Horn was placed in the custody of the only law enforcement official in Vanceboro, Washington County Deputy George Ross, who also operated the local fruit store. Horn confessed to dynamiting the railroad bridge. According to the New York Times, Deputy Ross didn’t know what to do with Werner Horn and “felt doubtful about detaining him much longer, fearing for his liability in the matter.” Ross said he had received no instructions from state or federal authorities, only railroad officials. The Sheriff of Washington County was contacted and told to take the prisoner for safekeeping to Machias, which he could only accomplish by a very circuitous route as the most direct route was through Canada. When the Sheriff complained that he had no grounds to charge Horn with any crime in the State of Maine, the federal authorities pointed out that the explosion in Vanceboro had broken many windows. Thus began a legal battle over Lt. Horn.

On its face, it seemed a relatively simple case. Lt. Horn had admitted to detonating 60 pounds of dynamite under an abutment at the Canadian end of the bridge and had been arrested within hours only a short distance from the scene of the crime. The Canadian government, through Britain, had demanded his extradition, and the people of Maine and the United States generally were largely sympathetic to the Allied cause. As the locals on both sides of the bridge were in favor of lynching the German, Deputy Ross had become more concerned with each passing hour. His understanding of the legal and diplomatic situation was limited, and it is not surprising the deputy did not comprehend the complexity of the problem. The crime was committed in Canada, and he was a Washington County deputy with no jurisdiction. He might have gained comfort from the fact that state and federal authorities were equally perplexed.

On February 3, 1915, the United States had not entered the war and was a neutral nation. This status carried significant international legal obligations when dealing with combatants. Lt. Horn had been activated by the German High Command at the beginning of the war and believed it his duty as a German officer to attack enemy military targets wherever possible. It was hard to argue a bridge over which munitions were carried to kill German soldiers was not a legitimate military target, and Lt. Horn had been careful to plant the explosives on the Canadian side of the bridge. It was, he claimed, an “Act of War” from which he was immune from extradition to Canada. U.S. authorities were in a quandary because this argument had support under international law, and further, the extradition treaty between the U.S. and Canada specifically exempted extradition for “political” offenses. The U.S. authorities needed to buy time, and Lt. Horn wanted desperately to put as much distance as he could between himself and the Canadian authorities because he truly feared he would be lynched if turned over to the Canadians. Horn agreed to make a deal with Deputy Ross. Because the explosion had broken a few windows on the U.S. side, Lt. Horn became a “willing party” to an agreement to plead to a charge of malicious mischief and accept a 30-day sentence in the Washington County jail in Machias. To his great relief, he was immediately transported to Machias via Bangor.

The Brits had been most unhappy about the denial of their extradition request. They kept the pressure on the U.S. They claimed the German military attaché in Washington, one Captain von Papen, and the German Ambassador were responsible for Lt Horn’s actions, not to mention numerous other crimes, plots, and unspeakable travesties against England, the U.S. and humanity in general. About a year after the Vanceboro bridge incident, the Brits, in exchange, gave von Papen safe conduct across the Atlantic to allow his return to Germany. When von Papen’s ship docked in England, he was, as agreed, sent along to Germany but with only the clothes on his back. All of his possessions, including official records, were seized by the British Secret Service on the dubious pretext that good conduct applied only to the persons, not their possessions. The howls of protest and anger that emanated from Germany could be heard even over the din of battle on the Western Front, but to no avail; the Brits had a treasure trove of intelligence, including von Papen’s checkbook. This, they claimed, contained an entry for a $700 payment to Lt Horn just before he attempted to blow up the bridge. The controversy raged for a couple of weeks in the New York Times and other papers but suddenly died for reasons unknown.

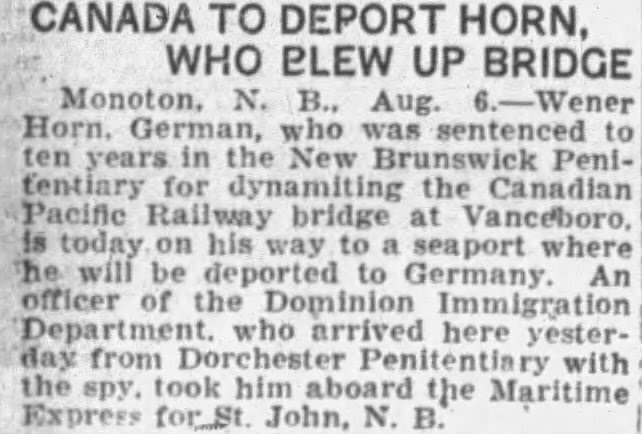

Ultimately, the British, or more accurately the Canadians, got their man. Because the United States had entered the war before Lt. Horn’s sentence expired, he was not released but instead was held in Georgia as an enemy alien. On September 27, 1919, he was brought to New York with a large group of German prisoners being repatriated to Germany, a fate he presumed he was to share. Instead, he was taken before a U.S. Commissioner at the request of the British Consul and asked if he had attempted to blow up the Canadian Pacific railroad bridge in McAdam. Always truthful, he answered, “Yes, I did it on behalf of my country, as an officer of the German Army, in wartime.” Horn was unrepresented at the hearing, and the extradition request was quickly granted. Upon his arrival in Canada, he was tried, convicted, and sentenced to 10 years to be served in Dorchester Prison in New Brunswick. On July 23, 1921, he was certified insane by physicians at Dorchester prison and returned to Germany. It was a sad fate to befall a young man of such undeniable courage and honesty.

EARLY SURRY VIRGINIA- FARRAR, JORDAN, PERRIN, ROYALL AND RANDOLPH TO THE FOUNDING FATHERS, JEFFERSON AND MARSHALL

EARLY SURRY VIRGINIA- FARRAR, JORDAN, PERRIN, ROYALL AND RANDOLPH TO THE FOUNDING FATHERS, JEFFERSON AND MARSHALL

William Farrar (1583 – c. 1637) was a landowner and politician in colonial Virginia. He was a subscriber to the third charter of the Virginia Company who immigrated to the colony from England in 1618. After surviving the Jamestown massacre of 1622 where ten settlers on Farrar’s land on the Appomattox River were killed, he got to Samuel Jordan’s 45-acre settlement at Jordan’s Journey. Jordan’s Journey was a palisaded fort that contained 11 buildings. After the attack, William Farrar stayed at Jordan’s Journey as it had become a relatively safe fortified rallying place for the survivors.

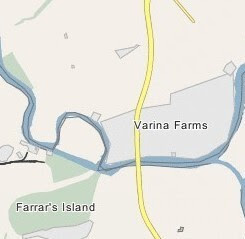

Samuel was a neighbor of John Rolfe and Pocahontas (see the map above showing Rolfe’s Varina Farms adjacent to Farrar’s Island). Samuel owned 2 plantations, had 20 slaves and many indentured servants whose fare he paid for their transportation to Virginia. He served as a burgess for Charles City. Samuel survived the massive Powhatan Indian attack of March 1622 at his plantation,

Samuel Jordan died before June 1623. Sometime afterward, Farrar proposed marriage to Jordan’s pregnant widow, Cecily, which involved him in the first breach of promise suit filed in North America. Reverend Greville Pooley claimed he had first proposed marriage three or four days after Samuel Jordan had died and Cecily had accepted. However, Cecily denied his proposal and accepted Farrar’s, which resulted in Pooley filing the suit. The case continued for almost two years. During the suit, Alexander Brown suggests that Farrar may have acted as Cecily’s legal representative. Eventually, Pooley signed an agreement in January 1624/5 that acquitted Cecily Jordan of her alleged former promises.

Even as the case was ongoing, William Farrar and Cecily Jordan continued to work together at Jordan’s Journey. In November 1623, Farrar was bonded to execute Samuel Jordan’s will regarding the management of his estate and Cecily Jordan was warranted to put down the security to guarantee Farrar’s bondage. During this time, “Farrar assumed the role of plantation ‘commander’ or ‘head of hundred'” for Jordan’s Journey. A year later, the Jamestown muster of 1624/25 lists “Farrar William Mr & Mrs. Jordan” as sharing the head of a Jordan’s Journey household with three daughters and ten manservants. During this time, Jordan’s Journey prospered. By May 1625 Farrar and Jordan were finally married, as it was then that Farrar was released from his bond to Jordan’s estate.

Farrar’s Island acquired its name after 1637 when the Farrar family obtained ownership as fulfillment the headright due to William Farrar, an early settler who was counselor and commissioner of the Crown Colony of Virginia. The Farrar family owned the peninsula until 1737 when it was sold to Thomas Randolph.

William and Cecily’s grandson Thomas married Katherine Perrin, the daughter of Richard and Katherine Royall Perrin. Katherine Royall Perrin was the daughter of Joseph Royall and Katherine Banks.

Joseph Royall’s plantation eventually grew to 1,100 acres, and he built a residence called Doghams, named after the French river D’Augham. Doghams was located on the banks of the James River above “Shirley Hundred”. This tract of land remained in the possession of the Royall family for almost 300 years.

When Joseph died in about 1665, Katherine became the wealthiest woman in America. Katherine was described as a beautiful red-haired lady who owned a gilded carriage, the wedding gift of her parents, which is said to have been linked with gold colored silk, drapes, and cushions of the same fabric.

The widowed Katherine married the widower Henry Isham. According to custom, Joseph Royall’s estate became the property of the new husband. Henry Isham added another wing onto the residence which was enhanced with tall pines and an English Flower Garden and was enclosed within a white picket fence. The structure still exists and is used as a horse farm as of 1995. Katherine and Henry Isham were the leaders of Virginia Society at that time.

Henry and Katherine’s daughter Mary married William Randolph. Her grandchildren included President Thomas Jefferson and the mother of Chief Justice John Marshall. Jefferson and Marshall were 2nd cousins once removed.

ROARING GIRL, LONDON’S SHARP-ELBOWED LOUDMOUTHED MARY FRITH

ROARING GIRL, LONDON’S SHARP-ELBOWED LOUDMOUTHED MARY FRITH

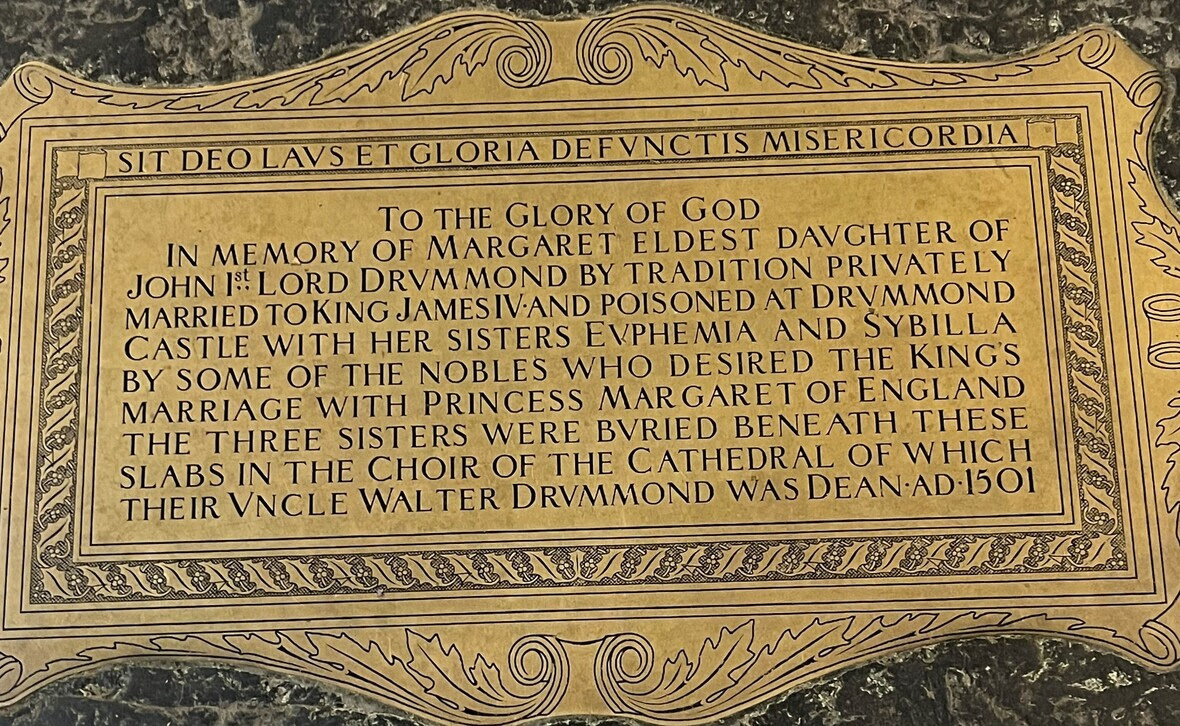

Mary Frith (1584 –1659), alias Moll (or Mal) Cutpurse, was a notorious English pickpocket and fence of the London underworld.

The facts of her life are incredibly confusing, with many exaggerations and myths attached to her name. The Life of Mrs. Mary Frith, a sensationalized biography written in 1662, three years after her death, helped to perpetuate many of these myths.

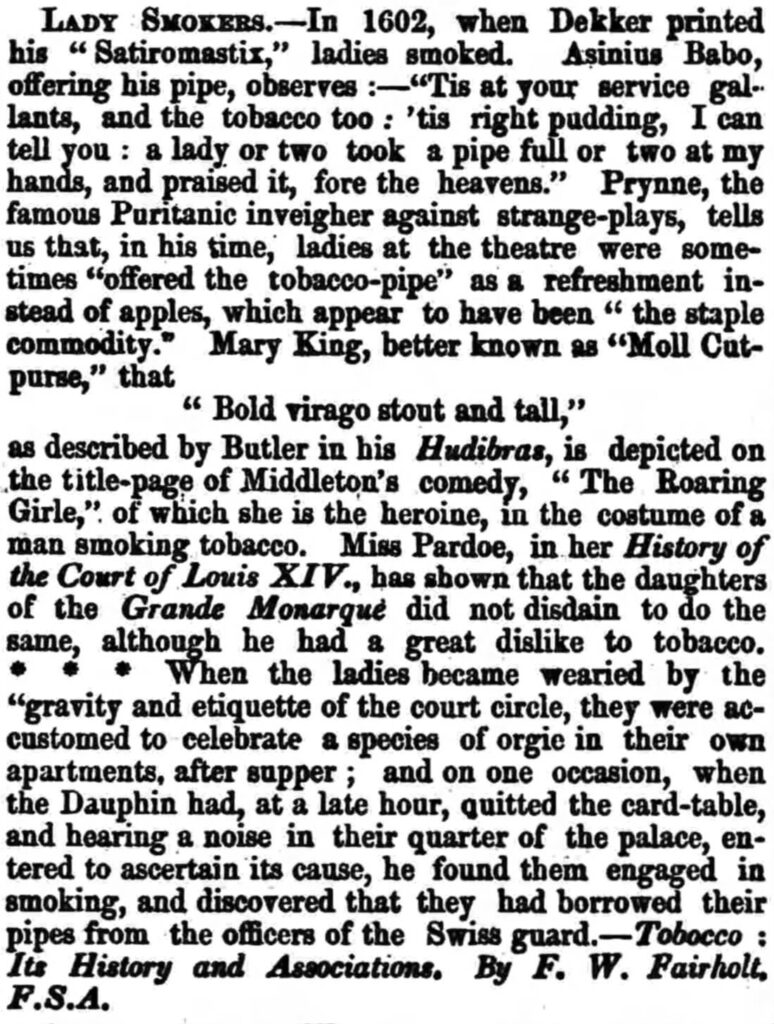

Mary Frith was born in the mid-1580s to a shoemaker and a housewife. Mary’s uncle, a minister and her father’s brother, once attempted to reform her at a young age by sending her to New England. However, she jumped overboard before the ship set sail and refused to go near her uncle again. Mary presented herself in public in a doublet and baggy breeches, smoking a pipe and swearing if she wished. She was recorded as having been burned on her hand four times, a common punishment for thieves. In February 1612, she was sentenced to do penance, standing and wearing a white sheet at St. Paul’s Cross during the Sunday morning sermon. It had little effect since she still wore men’s clothing and set mirrors up all around her house to stroke her vanity. Her house was surprisingly rather feminine due to the efforts of her three full-time maids. She kept parrots and bred mastiffs. Her dogs were particularly special to her: each had its bed with sheets and blankets. She prepared their food herself.

It is believed that she first became prominent in 1600 when she was indicted in Middlesex for stealing 2s 11d on August 26. It is at that point she began to gain notoriety. In the following years, two plays were written about her. First, the 1610 drama The Madde Pranckes of Mery Mall of the Bankside by John Day, the text of which is now lost. Another play (that has survived) came a year later by Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker, The Roaring Girl. Both works dwelt on her scandalous behavior, especially dressing in men’s attire, and did not show her in an especially favorable light. However, the surviving play is fairly complimentary of her by contemporary standards. The Roaring Girl, while highlighting her qualities that were deemed improper, also depicted her as possessing virtue, such as when she attacks a male character for assuming all women to be prostitutes and when she exhibits chastity by refusing ever to marry.

However, Mary seems to have been given fair freedom in a society that frowned upon women who acted unconventionally. In 1611, Frith even performed (in men’s clothing, as always) at the Fortune Theatre. She bantered with the audience and sang songs while playing the lute. It can be assumed that the banter and song were somewhat obscene, but by merely performing in public at all, she was defying convention.

Once, a showman named William Banks bet Mary 20 pounds that she would not ride from Charing Cross to Shoreditch dressed as a man. Not only did she win the bet, but she also rode, flaunting a banner and blowing a trumpet. She also rode Marocco, a famous performing horse.

Such public actions led to some reprisal. Frith was arrested for being dressed indecently on December 25, 1611, and accused of being involved in prostitution. On February 9, 1612, Mary was required to do a penance for her “evil living” at St Paul’s Cross. She performed then, according to a letter by John Chamberlain to Dudley Carleton. In his letter, Chamberlain observes, “She wept bitterly and seemed very penitent, but it is since doubted she was maudlin drunk, being discovered to have tippled off three quarts of sack”.

She married Lewknor Markham on March 23, 1614. It has been alleged that the marriage was little more than a clever charade. Evidence shows that the whole thing was contracted to give Frith a counter when suits against her referred to her as a “spinster”.

It turned out that society had some reason for its disapproval; by the 1620s, she was, according to her account, working as a fence and a pimp. She procured young women for men and respectable male lovers for middle-class wives. In one case where a wife confessed on her deathbed to infidelity with lovers that Mary provided, Mary supposedly convinced the woman’s lovers to send money for the maintenance of the children that were probably theirs. It is important to note that, at the time, women who dressed in men’s attire regularly were generally considered to be “sexually riotous and uncontrolled”, but Mary herself claimed to be uninterested in sex.

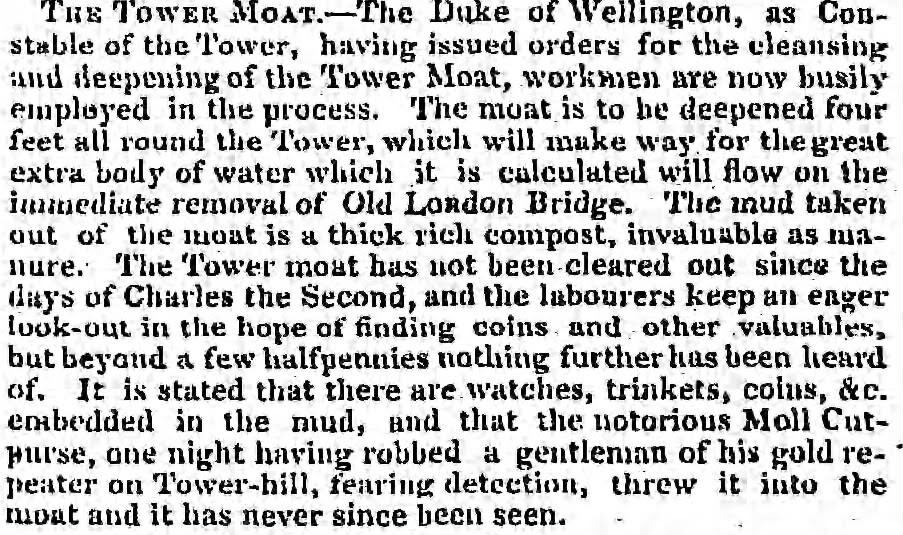

She is recorded as being released on June 21, 1644, from Bethlem Hospital after being cured of insanity, which may or may not be related to the (possibly apocryphal) story that she robbed General Fairfax and shot him in the arm during the English Civil War. It was said that to escape the gallows and Newgate Prison, she paid a £2,000 bribe.

She died of dropsy on July 26, 1659, on Fleet Street in London.

WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

Reach out to Dancestors Genealogy genealogists to research, discover, and preserve your family history. No one is getting any younger, and stories disappear from memory every year and eventually from our potential ability to find them.

Preserve your legacy, and the heritage of your ancestors.

Paper gets thrown in the trash; books survive!

So please do not hesitate and call me @ 214-914-3598 and get your project started!

ANCESTORS- DURING WWI, A GERMAN OFFICER TRIES TO BLOW UP A BRIDGE AT THE U.S.-CANADIAN BORDER AND IS SENTENCED TO ONLY 30 DAYS IN JAIL

ANCESTORS- DURING WWI, A GERMAN OFFICER TRIES TO BLOW UP A BRIDGE AT THE U.S.-CANADIAN BORDER AND IS SENTENCED TO ONLY 30 DAYS IN JAIL EARLY SURRY VIRGINIA- FARRAR, JORDAN, PERRIN, ROYALL AND RANDOLPH TO THE FOUNDING FATHERS, JEFFERSON AND MARSHALL

EARLY SURRY VIRGINIA- FARRAR, JORDAN, PERRIN, ROYALL AND RANDOLPH TO THE FOUNDING FATHERS, JEFFERSON AND MARSHALL ROARING GIRL, LONDON’S SHARP-ELBOWED LOUDMOUTHED MARY FRITH

ROARING GIRL, LONDON’S SHARP-ELBOWED LOUDMOUTHED MARY FRITH WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?