14 Jan Genealogist- Newsletter- January 13, 2023

Contents

- 1 MY UNCLE, A DEVELOPER, AND A HOBBY GENLEALOGIST TOLD ME THAT, GENERALLY, THE NORTHWEST PART OF CITIES WAS THE NICEST

- 2 WHAT IF CANADA INCLUDED TEXAS, WOULD A GENEALOGIST APPROVE?

- 3 HOW A GENEALOGIST MIGHT HAVE SAVED A FLEET

- 4 GREED GOT THE BEST OF THIS FOUNDING FATHER SAYS THE GENEALOGIST

- 5 THE U.S. JUST BIGGER BY THE EQUIVALENT OF ADDING ANOTHER TEXAS AND NEW MEXICO AS REPORTED BY A GENEALOGIST

- 6 PIGS CAUSE A LOT OF WARS, ACCORDING TO THIS GENEALOGIST

- 7 WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS, ASKS THE GENEALOGIST?

MY UNCLE, A DEVELOPER, AND A HOBBY GENLEALOGIST TOLD ME THAT, GENERALLY, THE NORTHWEST PART OF CITIES WAS THE NICEST

MY UNCLE, A DEVELOPER, AND A HOBBY GENLEALOGIST TOLD ME THAT, GENERALLY, THE NORTHWEST PART OF CITIES WAS THE NICEST

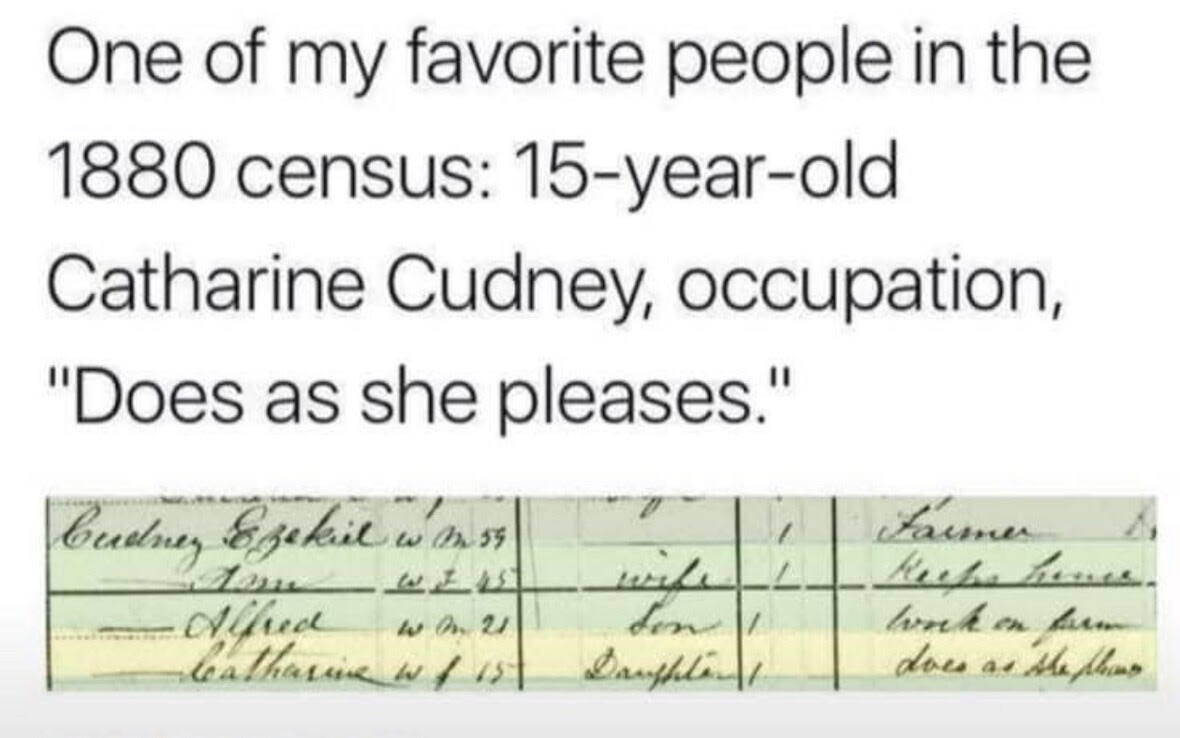

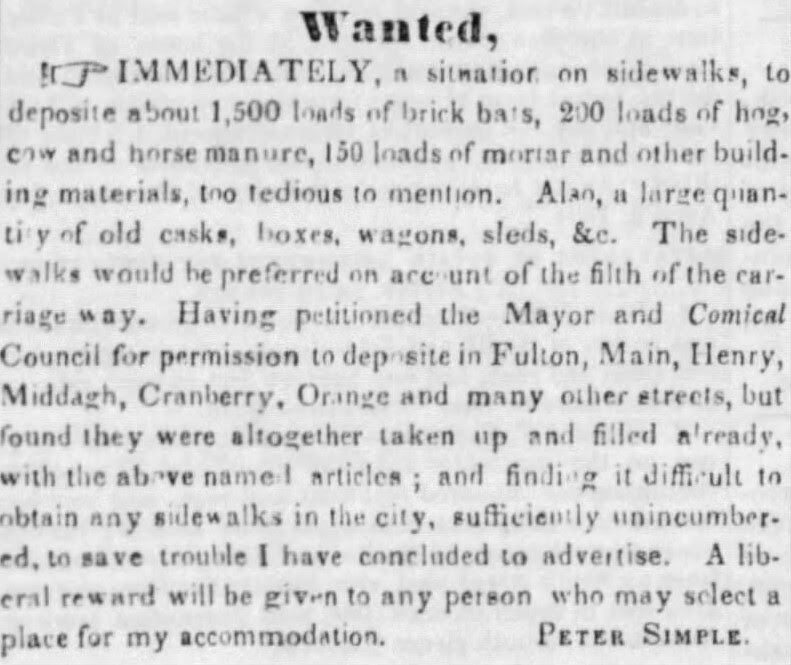

He said that was because the prevailing winds blow from northwest to southeast in North America, barring barriers like mountains. So, the bad smells of the affluent and the less all ended up in the southeast.

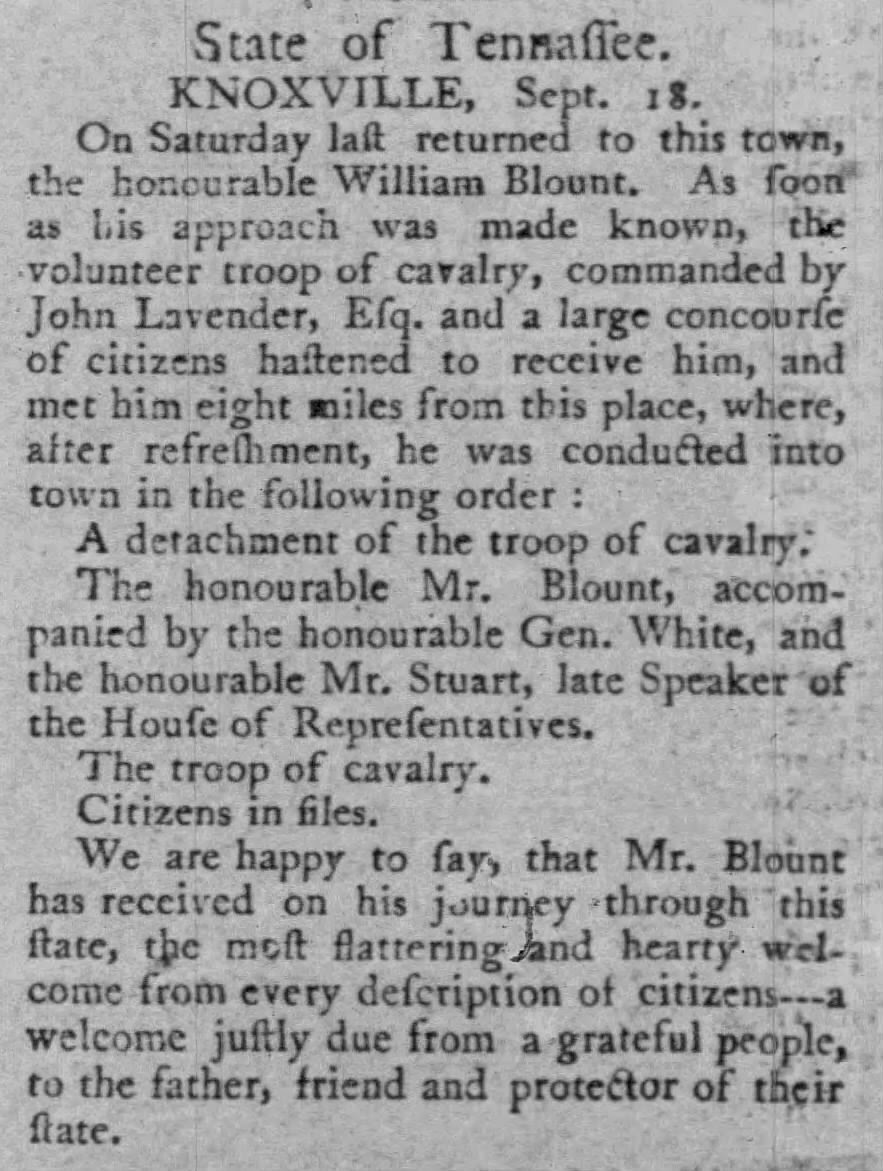

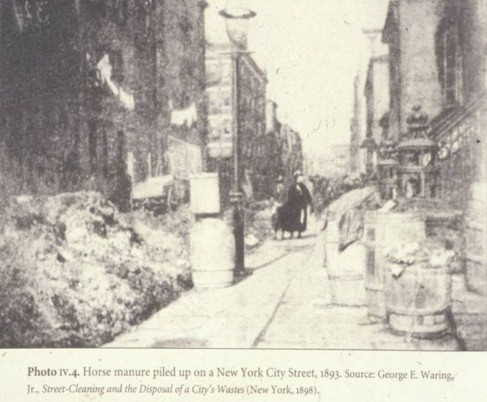

By 1894, the 15 to 30 pounds of manure produced daily by each beast multiplied by the 150,000+ horses in New York City resulted in more than three million pounds of horse manure per day that somehow needed to be disposed of. That’s not to mention the daily 40,000 gallons of horse urine.

In other words, cities reeked. As Morris (see the link for his article below) says, the “stench was omnipresent.” Here are some fun bits from his article:

Urban streets were minefields that needed to be navigated with the greatest care. “Crossing sweepers” stood on street corners; for a fee, they would clear a path through the mire for pedestrians. Wet weather turned the streets into swamps and rivers of muck, but dry weather brought slight improvement; the manure turned to dust, whipped up by the wind, choking pedestrians and coating buildings.

Even when removed from the streets, the manure piled up faster than it could be disposed of. Early in the century, farmers were happy to pay good money for the manure; by the end of the 1800s, stable owners had to pay to have it carted off. As a result of this glut, vacant lots in cities across America became piled high with manure; in New York, these sometimes rose to forty and even sixty feet.

One observer at the time said the streets were “literally carpeted with a warm, brown matting . . . smelling to heaven.” So-called “crossing sweepers” would offer their services to pedestrians, clearing out paths for walking, but when it rained, the streets turned to muck. And when it was dry, the wind whipped up the manure dust and choked the citizenry.

“We must remind ourselves that horse manure is an ideal breeding ground for flies, spreading disease. Morris reports that deadly outbreaks of typhoid and “infant diarrheal diseases can be traced to spikes in the fly population.” Genealogist.

Comparing fatalities associated with horse-related accidents in 1916 Chicago versus automobile accidents in 1997, he concludes that people were killed nearly seven times more often back in the good old days. The reasons for this are straightforward:

Horse-drawn vehicles have an engine with a mind of its own. The skittishness of horses added a dangerous level of unpredictability to nineteenth-century transportation. The former was particularly true in a bustling urban environment, with surprises that could shock and spook the animals. Horses often stampede, but a more common danger comes from horses kicking, biting, or trampling bystanders. Children were particularly at risk.

Falls, injuries, and maltreatment also took a toll on the horses. Data cited by Morris indicates that in 1880, more than three dozen dead horses were cleared from New York streets each day (nearly 15,000 a year).

In the late 1800s, the city hired drainage engineer George E. Waring Jr., who had worked on Central Park, to start cleaning things up. He pushed for new laws forcing owners to stable horses overnight (instead of leaving them in the streets) and mobilized crews to gather manure and horse corpses to be sold for fertilizer and glue, respectively. What they couldn’t sell was transported and dumped instead.

By the early 1900s, other factors were in motion — electric streetcars and internal combustion vehicles were gaining traction. Rising land pricing (for stables and farmland) and higher food costs increasingly made these new options more economical.

But the rise of private cars was the final nail in the horse-drawn coffin. By 1912, cars outnumbered horses on the streets of NYC, and by 1917, the last horsecar was put out of commission, and the issue of horse droppings slowly disappeared into history. Genealogist.

https://www.accessmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2016/07/Access-30-02-Horse-Power.pdf

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1080025/full

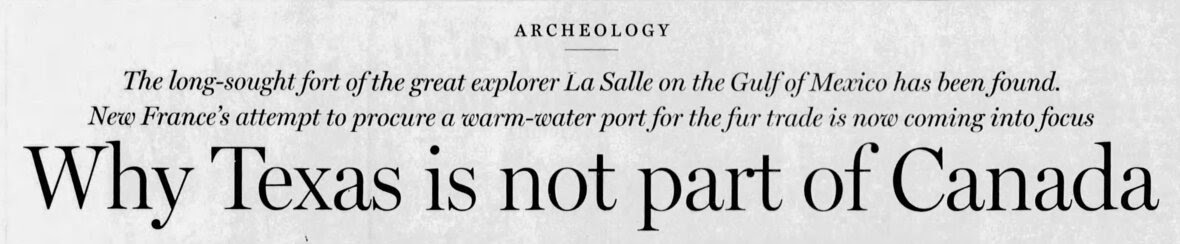

WHAT IF CANADA INCLUDED TEXAS, WOULD A GENEALOGIST APPROVE?

WHAT IF CANADA INCLUDED TEXAS, WOULD A GENEALOGIST APPROVE?

Henri Joutel was a French soldier and explorer who served in the last expedition commanded by French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. Joutel kept a detailed journal of his time in North America, including his experiences in what would become Arkansas.

Henri Joutel was born in Rouen, France, the hometown of La Salle, around 1643. Joutel’s father worked for La Salle’s family as a gardener. Joutel spent more than fifteen years in the French army and signed on as a member of the expedition that departed France on July 24, 1684. The third expedition organized by La Salle consisted of four ships and was tasked with establishing a colony along the Gulf Coast. Almost 300 soldiers and colonists embarked on the expedition, and Joutel was a close confidant of La Salle.

The ships arrived off the coast of what is now Texas in early 1685 and eventually created a temporary settlement on Matagorda Island. After losing some of the ships, the remainder returned to France, and the settlers moved to a new location on the mainland. By this time, only around 180 settlers remained after many died from disease, accidents, and confrontations with local Indians. Joutel was an important lieutenant, commanding the post while La Salle explored the countryside. La Salle planned to establish a colony along the Mississippi River and did not realize for more than a year that he had landed west of the river.

La Salle launched two expeditions to the east to find the river but was unsuccessful. During the expeditions, Joutel remained at the settlement. Joutel joined the third expedition, which departed the settlement on January 12, 1687, to reach Fort Saint Louis in current-day Illinois. Twenty-three colonists, including children, remained at the settlement, and seventeen men left on the expedition. The party members utilized several Indian guides to direct them, and they were passed off to new tribes as they traveled.

Growing short of supplies, a faction of the expedition attacked other members of the group, killing seven, including La Salle, on March 19. More were then killed, including La Salle’s killer and several other members of the expedition.

Joutel led the remaining six loyal expedition members to the northeast, crossing the Red River into Little River County on June 30. Over the next month, the group moved eastward, crossing the Little Missouri River on July 6 and the Ouachita River on July 11. On July 18, the party crossed the Saline River and reached the Arkansas River on July 24. Reaching the Mississippi River on July 29, the group moved upstream and left Arkansas the next day. Joutel’s journal records the tribes that the group interacted with and other details that he found interesting, such as the alligators he saw near Bayou Bartholomew.

The group ascended the Mississippi and reached Fort Saint Louis, where they wintered before going to Canada early the next year and making a report to authorities. They returned to France in late 1688. Upon the group’s return to Europe, Joutel obtained a job as a guard at one of the Rouen city gates.

In 1698, Louis de Pontchartrain began to organize an expedition to Louisiana to be led by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and requested a copy of Joutel’s journal to help the expedition. Joutel provided the journal but declined an offer to join the expedition. The journal was returned after the expedition with some pages missing, but it has still proven to be an invaluable resource to historians. Joutel died in Rouen around 1735. Genealogist.

HOW A GENEALOGIST MIGHT HAVE SAVED A FLEET

HOW A GENEALOGIST MIGHT HAVE SAVED A FLEET

Back around 2005, give or take a year, through a Friends of the Navy program, I had an opportunity to land via mail plane from San Diego on the USS Ronald Reagan Aircraft Carrier 80 miles off of Mexico. My group stayed in the officer’s quarters and was able to tour the ship (led by the chaplain) and observe flight operations.

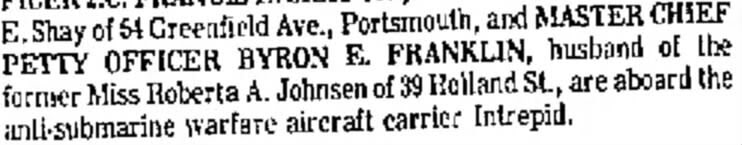

Before the trip, I contacted the ex-Navy ship people I know. One of them was my late father-in-law’s cousin, Byron Franklin, who I knew through working on family history. Byron was a retired Master Chief from the Navy (retired in 1978) who lived in Newport, RI. Byron said that if I got to go up on the bridge, ask the Quartermaster if they could turn their book to a specific page. I promised to do that, not knowing if I would take us on the bridge or what response I would get.

We got to tour the bridge, and when I was there, I asked for the Quartermaster. I shared the story, and he flipped this massive book (I remember the page number as being in the 700s), and he and his assistant read what was there.

The Quartermaster asked me if I knew this guy and how to contact him, which I shared. I am unsure what was in their book, but I suspect it related to the two navigation techniques bearing his name — the Franklin Piloting Technique and the Franklin Continuous Radar Plot.

Byron had previously shared with me his accomplishments in this regard. When he did that, I could sense some sour grapes as he perfected techniques about the time electronics arrived and took over the formerly manual navigation responsibilities.

In following up with Bryon about whether the Navy ever contacted him, he told me that the Naval War College in Newport had contacted him, and he was sharing his long-forgotten navigational techniques with the instructors. I imagine the interest came from the concern with tracking or jamming electronics and the need for dead reckoning skills. How cool is it that some retired sailor pushing 80 years of age could share his knowledge and skills with the modern generation of naval navigators?

So, if someday a Navy ship or fleet cannot use their electronics and has to rely on dead reckoning, I can take some comfort knowing that I contributed to the connection to bringing back lost skills to Navy ships.

The other good news is while on the bridge, I did not lean against any red buttons and start an accidental war with Mexico. Genealogist.

I have included a picture of Franklin plotting the course of the USS Intrepid Aircraft Carrier. For those needing to guide an aircraft carrier, links are below.

https://www.classypages.com/searcher/franklin.htm

https://www.navsource.org/archives/02/cv-11/11pf.htm

https://www.ion.org/publications/abstract.cfm?articleID=101248

GREED GOT THE BEST OF THIS FOUNDING FATHER SAYS THE GENEALOGIST

GREED GOT THE BEST OF THIS FOUNDING FATHER SAYS THE GENEALOGIST

William Blount (1749 –1800) was an American politician, landowner, and Founding Father who was one of the signers of the Constitution of the United States. He was a member of the North Carolina delegation at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and led the efforts for North Carolina to ratify the Constitution in 1789 at the Fayetteville Convention. He then served as the only governor of the Southwest Territory and played a leading role in helping the territory gain admission to the union as the state of Tennessee. He was selected as one of Tennessee’s initial United States Senators in 1796, serving until he was expelled for treason in 1797.

Born to a prominent North Carolina family, Blount served as a paymaster during the American Revolutionary War. He was elected to the North Carolina legislature in 1781, where he remained in one role or another for most of the decade, except for two terms in the Continental Congress in 1782 and 1786. Blount pushed efforts in the legislature to open the lands west of the Appalachians to settlement. As governor of the Southwest Territory, he negotiated the Treaty of Holston in 1791, bringing thousands of acres of Indian lands under U.S. control.

Throughout the 1780s and 1790s, William Blount and his brothers gradually bought up large amounts of western lands, acquiring over 2.5 million acres by the mid-1790s. Much of this land was bought on credit, pushing the family deeply into debt. In 1795, the market for western lands collapsed, and land prices plummeted. Many land speculators, including Blount associate David Allison, went bankrupt. Blount partnered with Philadelphia physician Nicholas Romayne to sell land to British investors, but their efforts were unsuccessful. Compounding Blount’s problems, Timothy Pickering, who despised Blount, replaced Henry Knox as secretary of war in 1795.

Following France’s defeat of Spain in the War of the Pyrenees, land speculators, already on the financial brink, worried that the French would eventually gain control of Spanish-controlled Louisiana and shut off American access to the Mississippi River. In hopes of preventing this, Blount and his friend, Indian agent John Chisholm, concocted a plan to allow the British to gain control of Spanish-controlled Louisiana and Florida, expecting them to give free access to New Orleans and the Mississippi River to American merchants. The plan called for American territorial militias, with the aid of the British Royal Navy, to attack New Madrid, New Orleans, and Pensacola.

To help carry out the plan, Blount recruited Romayne, who never showed more than lukewarm support for the idea, and Knoxville merchant James Carey. Chisholm, meanwhile, sailed to England to recruit British supporters for the plan. In April 1797, Carey was at the Tellico Blockhouse near Knoxville when he gave a government agent a letter from Blount outlining the conspiracy. The agent turned the letter over to his superior, Colonel David Henley, in Knoxville, and Henley sent it to Pickering. Elated at the opportunity to crush Blount, Pickering turned the letter over to President John Adams.

Determining that the actions of Blount, a senator from Tennessee, constituted a crime, Adams sent Blount’s letter to the Senate, where it was presented on July 3, 1797, while Blount was out for a walk. When Blount returned, the clerk read the letter’s contents aloud as Blount stood in stunned silence. Vice President Thomas Jefferson asked Blount if he had written the letter. Blount gave an evasive answer and asked that the matter be postponed until the following day, which was granted. On July 4, Blount refused to return to the Senate and had Cocke reread a letter requesting more time. The Senate rejected this request and formed an investigative committee. Ordered to testify before the committee, Blount initially attempted to flee by ship to North Carolina, but federal deputies seized the ship and most of his belongings. On July 7, Blount, after consulting with attorneys Alexander Dallas and Jared Ingersoll, testified before the committee and denied writing the letter. The following day, the House of Representatives voted 41 to 30 to hold impeachment hearings, and the Senate voted 25 to 1 to “sequester” Blount’s seat, effectively expelling him, with Henry Tazewell casting the lone dissenting vote.

Rather than await trial, Blount posted bail and fled to Tennessee. Chisholm remained in England in a debtors’ prison for several months and confessed the entire scheme upon his return. Romayne was arrested and forced to testify before the committee, where he admitted to his part in the conspiracy. The House continued to consider evidence for Blount’s impeachment in early 1798. At one session on January 30, a bizarre brawl erupted between two congressmen, Matthew Lyon and Roger Griswold, concerning the hearings. The Senate convened as a Court of Impeachment for the impeachment trial on December 17, 1798; though Blount refused to attend, despite a visit to Knoxville from the Senate sergeant-at-arms, the Senate heard arguments from his counsel, who argued lack of jurisdiction because Blount had not been an officer within the meaning of Article II, nor was he now an officer since he had been expelled and now held no federal office. On January 11, 1799, the Senate voted 14 to 11 to dismiss the impeachment for lack of jurisdiction. The ruling left unclear which (or both) of the two arguments were dispositive, though it became generally accepted that impeachment did not extend to senators.

The unraveling of the conspiracy destroyed Blount’s reputation at the national level and touched off a series of accusations between Federalists and Anti-federalists. George Washington called for swift justice against Blount and hoped he would be “held in detestation by all good men.” Abigail Adams called the conspiracy a “diabolical plot” and lamented the fact that there was no guillotine in Philadelphia. Pickering argued that the conspiracy was part of a greater French plot and accused Thomas Jefferson of involvement. Oliver Wolcott suggested the conspiracy was an attempt to blackmail Spain. Genealogist.

President John Adams later fired Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, the first ever cabinet member to be dismissed.

THE U.S. JUST BIGGER BY THE EQUIVALENT OF ADDING ANOTHER TEXAS AND NEW MEXICO AS REPORTED BY A GENEALOGIST

THE U.S. JUST BIGGER BY THE EQUIVALENT OF ADDING ANOTHER TEXAS AND NEW MEXICO AS REPORTED BY A GENEALOGIST

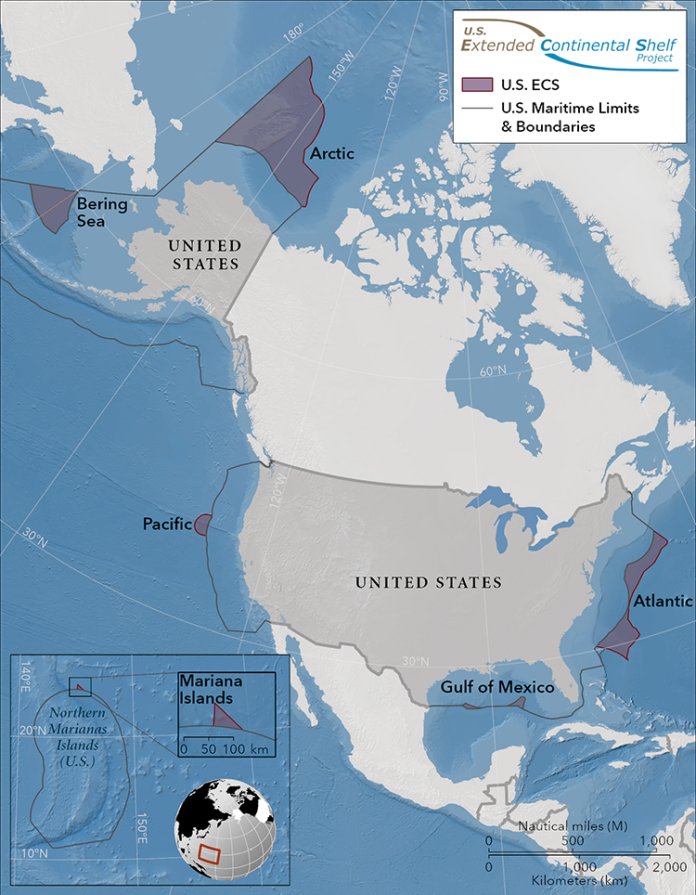

Tuesday, the United States grew by a million square kilometers — the equivalent of nearly 60% of Alaska’s land mass.

The State Department enlarged the country’s geography, citing international Law, by defining how far the continental shelf extends under the sea. The new additions are spread across seven ocean areas, and more than half of the claim is in the Arctic.

“America is larger than it was yesterday,” said Mead Treadwell, a former Alaska lieutenant governor and former chair of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission. “It’s not quite the Louisiana Purchase. It’s not quite the purchase of Alaska, but the new area of land and subsurface resources under the land controlled by the United States is two Californias larger.”

State Department project director Brian Van Pay said it took multi-agency fieldwork spanning 20 years for scientists to gather data about the shape of the seafloor and measure sediment layers.

“Forty missions at sea, going to areas that we’ve never explored before, finding entire seamounts we didn’t even know existed,” Van Pay said. “And, if you add up all the time that our scientists spent at sea, it’s over three years of data collection.”

The State Department says the extended continental shelf claim was made according to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea provisions. The U.S. Senate has never ratified that treaty, but after 40 years, the government is announcing its continental shelf limits anyway.

Treadwell says it’s a unilateral move but a solid one.

“If somebody came back and said, ‘Your science is bad,’ I think the United States would listen,” Treadwell said. “But I don’t think science is bad. I think we’ve had very good science.”

The State Department’s recognition of its extended continental shelf in the Arctic doesn’t conflict with a 1990 agreement setting the maritime boundary with Russia.

“None of the fixed points delineating the outer limits of the continental shelf of the United States are located west of the agreed boundary with the Russian Federation,” the State Department said in a summary explaining its announcement.

Van Pay said Canada is likely to have an overlapping claim that can be negotiated later.

The U.S. and other countries claim 200 miles off their coasts as exclusive economic zones. They exercise rights in these zones over the resources in the seabed and the waters above.

Tuesday’s declaration of the extended continental shelf, beyond 200 miles from shore, doesn’t include jurisdiction over the water column or fishing rights. Still, it gives the federal government control over the seafloor and any valuable resources that can be mined from it and the right to say who can conduct research or lay pipelines across it.

Some of the areas of ocean the U.S. has claimed as extended continental shelf are in the Atlantic, the Pacific, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Mariana Islands. Looking at the map, the larger section north of Alaska plus a smaller patch in the Bering Sea total nearly the acreage of Texas. Genealogist.

By Liz Ruskin, Alaska Public Media -December 20, 2023

PIGS CAUSE A LOT OF WARS, ACCORDING TO THIS GENEALOGIST

We recently visited the French legation in Austin, TX, and I learned about the Pig War. While looking for more information on this, I found out that pigs cause a lot of wars; here are three before I get to the article on the Republic of Texas dispute with France.

The so-called Saukrieg (“Pig War”) of 1555–1558 was a feud between John of Carlowitz and Zuschendorf (pictured above) and the Bishop of Meißen, John IX of Haugwitz. During the feud, Carlowitz had 700 pigs, belonging to the bishop’s subjects, driven away to pursue his claims, which explains the rather unusual name of the feud. The Saukrieg has been described as the last feud “in the spirit of the Middle Ages”.

The Pig War was a confrontation in 1859 between the United States and the United Kingdom over the British–U.S. border in the San Juan Islands, between Vancouver Island (present-day Canada) and the State of Washington (map above). The Pig War, so called because the shooting of a pig triggered it, is also called the Pig Episode, the Pig and Potato War, the San Juan Boundary Dispute, and the Northwestern Boundary Dispute. Despite being referred to as a “war”, neither side had human casualties.

The Pig War, or Customs War, was a trade war between Austria-Hungary and the Kingdom of Serbia from 1906 to 1908, during which the Habsburgs unsuccessfully imposed a customs blockade on Serbian pork.

Pig War is the name given to the dispute between Alphonse Dubois de Saligny (pictured above), French chargé d’affaires, and the Lamar administration, resulting in a temporary rupture of diplomatic relations between France and the Republic of Texas. It originated in 1841 in a private quarrel between the Frenchman and an Austin hotelkeeper, Richard Bullock, over marauding pigs. Dubois de Saligny complained that the pigs, owned by Bullock, invaded the stables of his horses, ate their corn, and even penetrated his very bedroom to devour his linen and chew his papers. Bullock, charging that the Frenchman’s servant had killed a number of his pigs on orders from his master, thrashed the servant and threatened the diplomat himself with a beating. Dubois de Saligny promptly invoked the “Laws of Nations,” claimed diplomatic immunity for himself and his servant, and demanded the summary punishment of Bullock by the Texas government. The Frenchman was already on bad terms with the administration, especially acting president David G. Burnet and Secretary of State James S. Mayfield, who opposed Dubois’s project of a Franco-Texan commercial and colonization company (although Mayfield had originally introduced the Franco-Texian Bill in the House). Dubois may have exploited the undignified wrangle with Bullock as a means to vent his spleen on the current administration of the republic. When Mayfield refused to have the hotelkeeper punished without due process of law, the chargé d’affaires, acting without his government’s instructions, broke diplomatic relations and left the country in May 1841. From Louisiana, where he resided for more than a year, he emitted occasional dire warnings of the terrible retribution that France would exact.

While the French government officially supported its agent in his quarrel with Texas, it disapproved of his highhanded departure from his post. It had no intention of resorting to force on behalf of this undiplomatic and short-tempered subordinate. Thus, the “war” ended in a compromise. The Houston administration, which succeeded that of Lamar, made “satisfactory explanations” to the French government and requested the return of Dubois de Saligny. These explanations were less than Saligny had asked for, as they contained neither censure of the previous administration nor promises to punish Bullock. But aware of disapprobation in the French Foreign Ministry, he accepted this peace offering and returned to Texas in April 1842 to resume his official duties. The Pig War was an isolated episode in the history of the Texas frontier with few repercussions. A black mark against Dubois de Saligny in the French Foreign Ministry hurt his career, but it did not alter France’s policy toward the young republic. Genealogist.

WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS, ASKS THE GENEALOGIST?

WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS, ASKS THE GENEALOGIST?

Reach out to Dancestors Genealogy genealogists to research, discover, and preserve your family history. No one is getting any younger, and stories disappear from memory every year and eventually from our potential ability to find them.

Preserve your legacy, and the heritage of your ancestors.

Paper gets thrown in the trash; books survive!

So please do not hesitate and call me @ 214-914-3598 and get your project started!

MY UNCLE, A DEVELOPER, AND A HOBBY GENLEALOGIST TOLD ME THAT, GENERALLY, THE NORTHWEST PART OF CITIES WAS THE NICEST

MY UNCLE, A DEVELOPER, AND A HOBBY GENLEALOGIST TOLD ME THAT, GENERALLY, THE NORTHWEST PART OF CITIES WAS THE NICEST WHAT IF CANADA INCLUDED TEXAS, WOULD A GENEALOGIST APPROVE?

WHAT IF CANADA INCLUDED TEXAS, WOULD A GENEALOGIST APPROVE? HOW A GENEALOGIST MIGHT HAVE SAVED A FLEET

HOW A GENEALOGIST MIGHT HAVE SAVED A FLEET GREED GOT THE BEST OF THIS FOUNDING FATHER SAYS THE GENEALOGIST

GREED GOT THE BEST OF THIS FOUNDING FATHER SAYS THE GENEALOGIST THE U.S. JUST BIGGER BY THE EQUIVALENT OF ADDING ANOTHER TEXAS AND NEW MEXICO AS REPORTED BY A GENEALOGIST

THE U.S. JUST BIGGER BY THE EQUIVALENT OF ADDING ANOTHER TEXAS AND NEW MEXICO AS REPORTED BY A GENEALOGIST WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS, ASKS THE GENEALOGIST?

WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS, ASKS THE GENEALOGIST?