10 Aug Genealogy Newsletter- August 13, 2022

Contents

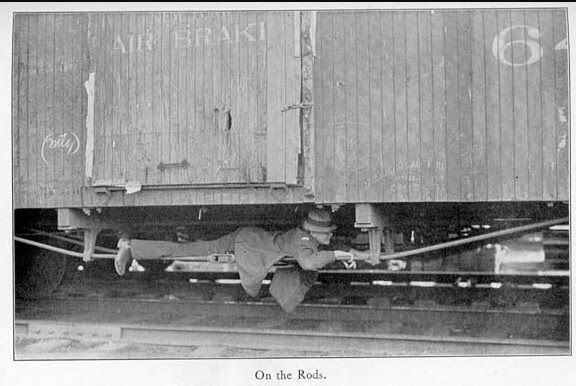

GENEALOGY- IN CASE YOU EVER WANT TO BE A TRAINRIDER HERE ARE SOME TIPS!

GENEALOGY- IN CASE YOU EVER WANT TO BE A TRAINRIDER HERE ARE SOME TIPS!

While on a recent trip up to the border of Montana and Idaho, I met a “trainrider”. He and three of his train riding buddies now worked at a mountain café. He shared tales that reminded me of my grandfather’s stories of riding the rails in the 1930s during the depression. Of course, back then, they were called hobos. Here is some insight into the early “trainriders.”

The hobo is familiar as a character from kitsch art and silent film and feels like a romantic caricature today. But these traveling hobos were real — and they honed surprisingly complex strategies for riding the rails.

There may have been a million hobos in 1915 … and they needed to keep moving

The term “hobo” loosely defines everything from happy-go-lucky train hoppers to large homeless communities (and sometimes derogatorily so). But in its most popular definition, itinerant workers traveling the country by train use the word to describe themselves and their unique and intentional lifestyle. There was and still is a proud tradition of self-identified hobos.

These hobos were most active from the 1890s through the 1930s. It isn’t easy to know how many there were (since part of their goal was to avoid detection), but one 1915 estimate put their population at

1 million. And their ranks swelled during the Great Depression as work became scarce.

Hobos tended to have a particular character, too. Sociologist Nels Anderson wrote about them in his groundbreaking 1923 book The Hobo. Though he dealt with large homeless communities that were the opposite of carefree, he also identified a particular hobo group that followed “the American tradition; of pioneering, wanderlust, [and] seasonal employment.” This was the group that proudly called itself “Hobohemia.”

Hobohemia was home to the peculiar dreamers, small-time criminals, and railroad experts we imagine when we hear “hobo” today. These itinerant workers were experts at hopping on and off trains and liked to brag about it, too, since it could be incredibly dangerous.

When hobos were common, most believed the private police were a bigger threat than civil police forces.

That may be because the railroads had more reason to dislike hobos. In addition to riding the rails, hobos occasionally broke into boxcars and stores, which spoiled goods both on the train and in communities near train routes, endangering a railroad’s operation through the town.

That meant civil police — the hobo-labeled “town clowns” — were usually more focused on kicking hobos out of town than on jailing them.

But railroad police couldn’t avoid the hobo problem. Called “bo chasers” and “car-seal hawks,” they adopted extremely aggressive tactics. They took it as their job to terrorize those who rode the rails, often by any means necessary. In addition to bouncing out hobos on trains, they often threw stones at hobos or shot them. “He is a hunter,” Anderson wrote of the railroad officer, “and the tramp is his prey.”

All that led to a staggering death toll. In 1920, 2,166 trespassers were killed and 2,363 were injured on trains or in railroad yards. That led hobos to do whatever they could to avoid being spotted.

Keeping the railroad police in mind, what was the best way to hop a train car?

1) Finding an empty car. This was ideal. It gave hobos space to stay without the threat of being crushed by shifting goods or injured during a bumpy ride. Occasionally, hobos even tore up the floors of these empty cars for firewood.

2) Hiding between cars. Most hobos also liked “riding the blinds” by swinging onto the front end of a baggage car. The location between cars helped them avoid being spotted by railroad police. Though there was a threat of being crushed between cars, the ability to avoid detection made it relatively safe.

3) Riding on top. To “deck” a car was extremely dangerous since it was easy to be thrown off the top of the train. Author Jack London, who did his own time riding the rails, wrote about the practice in The Road: “And let me say right here that only a young and vigorous tramp is able to deck a passenger train, and also, that the young and vigorous tramp must have his nerve with him as well.”

If that didn’t work, there was another heart-racing option.

4) Riding beneath the train:

Today, “riding the rails” is synonymous with any travel on a train. But in the past, it occasionally referred to the specific act of riding rails underneath train cars.

Older trains required support trusses for heavier cargo, giving space for hobos to ride under the train (those rods were abandoned with the advent of stronger steel cars around the 1930s). It was extremely dangerous, but there was an advantage: the conductor couldn’t kick you out until the train stopped.

Unfortunately, the rods came with a lot of risks. As London described, a cruel brakeman could lower a pin on a rope underneath the train, where it would smack up and down against the bottom of the rods, battering hobos underneath until they were beaten or killed. And that wasn’t the only dangerous option.

5) Riding in refrigerator cars. London spent a glorious night in a refrigerated car. He burned papers on the floor and slept like a baby through the night.

These ice-cooled cars were not only a break from hot temperatures but also carried food and could store hobos’ food. But for many hobos, refrigerated cars were death traps.

Usually, only hobos who didn’t know any better would go inside the car. That’s because railroad police were aware of the temptation and were known to lock hobos inside to freeze. As a result, men froze to death in the refrigerator cars, as Maury “Steam Train” Graham recalled in Tales of the Iron Road: My Life as King of the Hobos.

6) Trying everything else. There were other, more dangerous riding places too. As described in American Tramp and Underworld Slang, written by Godfrey Irwin in 1971, hobos could also ride as “blind baggage tourists” (pretending they had tickets), as “open-air navigators” (on top of open freight), or as “bumper riders” (standing on the couplers between cars).

But all those inventive, adrenaline-pumping tactics had an expiration date.

By the end of the 1930s, the hobo rail-riding phenomenon had faded due to various factors, including the improving economy. As the century continued, increasing freight train speed, more trucking, and new laws made hobos rarer. As trains got faster, it became harder to hop them, and hitchhiking probably took some of the population as well. Rail-riding hobos didn’t disappear, but they became much less common.

Still, Hobohemia hasn’t completely disappeared. A culture of hobos ensured that — which may be why there are still hobo conventions even today. And some of the attendees will probably take a nice train to get there.

By Phil @vox.com Jun 9, 2015

GENEALOGY SHE WAS BORN ON A SAN FRANCISCO STREET CORNER DELIVERED BY A RANDOM DUDE. 30 YEARS LATER THEY MEET

GENEALOGY SHE WAS BORN ON A SAN FRANCISCO STREET CORNER DELIVERED BY A RANDOM DUDE. 30 YEARS LATER THEY MEET

Until Wednesday morning, Patrick Combs had not seen Searcy Hughes since she was born June 29, 1988, an occasion noted on the front page of the next morning’s Chronicle.

“Searcy,” Combs called out as if recognizing her before dashing across Hayes Street to meet Hughes for a long embrace in front of some bewildered tourists looking for the Painted Ladies.

“How are you?” he asked. “Good,” she said. “How are you?”

Combs, 56, flew in from San Diego and Hughes, 34, came from South Dakota just for this extraordinary reunion. They walked arm in arm to 580 Fell St. so Combs could re-enact their prior meeting, the details of which were so astonishing that each of the crucial details earned its own paragraph in the 1988 Chronicle story.

“A funny thing happened to Patrick Combs on his way to work yesterday.

He delivered a baby.

On the sidewalk.

While a crowd of people watched.

Then he fell in love with the little girl he brought into the world, a little girl he worried he would never see again.”

That last part turned out to be true on Combs’ end because he worried about it for 34 years, never knowing the name of the baby he helped deliver.

But Hughes found his name after she tracked down the Chronicle story of her birth and located Combs in San Diego, where he works as a motivational speaker for businesses and executives.

The baby girl, named Crystal by her birth mother, was soon given up for adoption and raised mostly in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

“I vaguely knew that the story of my birth was sort of a big deal,” said Hughes, who is a prison guard in Sioux Falls, S.D. “So I asked a friend to type the keywords ‘Crystal,’ ‘baby,’ and ‘born on the street’ into the Ancestry.com website.” The friend got an immediate hit to The Chronicle story, and the mystery was solved.

“Suddenly, the story I heard my whole life about being born on the street by some random dude that I didn’t even know was true turned out to be very real,” she said. “Getting that proof was a huge solidifying moment.”

Facebook helped her find him, which led to a video he posted telling her birth story. Then, on Thanksgiving of 2019, she sent a Facebook message saying, “I keep typing ‘hi Patrick,’ and it just doesn’t feel like enough.”

Combs saw that first sentence as he was driving in his car, and knowing what was coming, he pulled over and broke into tears.

“You are the man who caught me when I was born … I am searching for answers.” Combs had been waiting to tell her the story her entire life.

“I thought this would be the great mystery of my life to which I would never see the answer. Then, when I realized she had somehow found me, this huge giant crescendo of a wave rolled through my soul.”

“I’ve waited 31 years hoping for this moment,” he messaged her two days later. Knowing how emotional it would get, they waited a few weeks before talking on the phone, when she sprung on him her main question: Did he know the name of her birth mother?

He did. Bonnie Bennett. Her subsequent search for her was not as successful. Bennett died just six months after her daughter was born, of a drug overdose in San Francisco, at age 23.

“I was deeply wanting to know what happened to that baby born on the sidewalk,” he said, “so when she reached out to me, it was just an astonishing miracle that I thought would never happen. It was like an answered prayer.”

The prayer played out as he approached his old apartment building and said, “OK. Here we go,” before he detailed coming out of the building around 7 a.m. and heading down the street toward his job at Levi Strauss & Co. when he saw a woman down on the sidewalk.

“She said, ‘Call me an ambulance. I’m pregnant,’” Combs said. He deduced she had crawled up some steps from a light well but made it no farther. Knocking on doors, he finally got into a building to call 911.

By the time he returned to the woman on the sidewalk, “you were on your way,” he said to Hughes. “I told your mother, ‘Don’t be afraid,’ then I moved into position, and your mom did the most heroic act.”

When the baby landed in his hands, he at first thought she was dead. “Then your eyes popped open like the headlights on a Fiat. Then you looked at me and started crying.” At which point the medics finally arrived.

“I didn’t remember what your mother looked like until I saw you,” he said to Hughes. “That’s how much you look like her.”

Reliving that long-ago morning this morning was overwhelming, and Combs and Hughes engaged in a longer and tighter hug than the earlier one.

“It definitely hit me super hard, but it’s not a sad feeling,” Hughes said after taking off her shades to wipe her eyes.

“It’s a feeling that so much awesome humanity happened right here on the sidewalk.”

Sam Whiting is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: Twitter: @SamWhitingSF

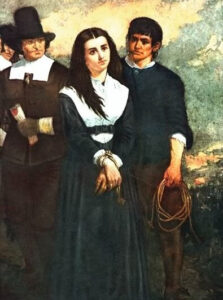

GENEALOGY THE FINAL SALEM WITCH EXONERATED AFTER 329 YEARS IN WITCH JAIL

GENEALOGY THE FINAL SALEM WITCH EXONERATED AFTER 329 YEARS IN WITCH JAIL

Although the last Salem witch trial was held in May 1693, public response to the events continued. In the decades following the trials, survivors and family members (and their supporters) sought to establish the innocence of the convicted individuals and gain compensation. In the following centuries, the descendants of those unjustly accused and condemned have sought to honor their memories. Events in Salem and Danvers in 1992 were used to commemorate the trials. In November 2001, years after the celebration of the 300th anniversary of the trials, the Massachusetts legislature passed an act exonerating all who had been convicted and naming each of the innocent, except for Elizabeth Johnson,

The final outstanding woman convicted of witchcraft in the Salem Witch Trials has finally been exonerated due to the dogged pursuits of a Massachusetts eighth-grade teacher and her students.

Andover resident Elizabeth Johnson Jr. was sentenced to death in 1693 for witchcraft. However, she was exonerated after Carrie LaPierre, a North Andover Middle School teacher, spent three years lobbying for her acquittal with her students. They finally cleared the old non-witch’s name as part of a $53 billion state budget plan signed by Governor Charlie Baker on Thursday.

LaPierre spoke to the New York Times on Sunday about saving the victim of a witch hunt, saying she was “excited and relieved” but also disappointed that she couldn’t share the moment with her students, who are currently on summer vacation. It must be nice. According to LaPierre, Elizabeth Johnson Jr. was 22 when she was accused and was likely targeted for having a mental disability and being childless and unwed.

Why she was the only non-witch left in the books as a for-sure witch is likely because other exonerations came after descendants — of which Elizabeth Johnson Jr. had none — campaigned for them. Another theory is that her mother, accused of witchcraft, had the same name and had already been exonerated. Another theory from me is these guys (the guys in charge) suck and are lazy. So why didn’t they go … okay we’re going to exonerate all these witches at once? Why did it take three years of students lobbying the governor and writing letters to get them to say, okay, we give — she’s not a witch? Unclear to me.

Regardless, we are, as ever, the granddaughters of the witches you couldn’t burn, like Elizabeth Johnson Jr., who is today officially exonerated of her crime of being childless and possibly mentally disabled. Nevertheless, she persisted in not being a witch officially. We have to take our wins where we can get them, mamas.

GENEALOGY- YOUR ANCESTORS ARE WAITING FOR YOU TO DISCOVER THEM!

GENEALOGY- YOUR ANCESTORS ARE WAITING FOR YOU TO DISCOVER THEM!

Reach out to Dancestors and let us research, discover, and preserve your family history. No one is getting any younger, and stories disappear from memory every year and eventually from our potential ability to find them. Paper gets thrown in the trash, books survive! So do not hesitate, and call me @ 214-914-3598.

GENEALOGY- IN CASE YOU EVER WANT TO BE A TRAINRIDER HERE ARE SOME TIPS!

GENEALOGY- IN CASE YOU EVER WANT TO BE A TRAINRIDER HERE ARE SOME TIPS!

GENEALOGY- YOUR ANCESTORS ARE WAITING FOR YOU TO DISCOVER THEM!

GENEALOGY- YOUR ANCESTORS ARE WAITING FOR YOU TO DISCOVER THEM!