14 Dec Genealogist Newsletter- December 15, 2024

Contents

- 1 GENEALOGIST- ONE KILLING LEADS TO ANOTHER 20 YEARS LATER

- 2 GENEALOGIST- COUSIN LANCELOT

- 3 GENEALOGIST- A TONY AND TONY STORY FROM ONE OF OUR CLIENTS

- 4 GENEALOGIST- THE DONUT STORIES

- 5 SO, WHAT’S THE REAL STORY- PART II

- 6 GENEALOGIST CHARLOTTE DUPUY VS. HENRY CLAY

- 7 GENEALOGIST HENRY CLAY’S SUFFRAGETTE GREAT GRANDAUGHTER

- 8 FOREIGN VISITORS SPENDING THE NIGHT IN RURAL AMERICA

- 9 GENEALOGIST WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS KNOWING ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

GENEALOGIST- ONE KILLING LEADS TO ANOTHER 20 YEARS LATER

GENEALOGIST- ONE KILLING LEADS TO ANOTHER 20 YEARS LATER

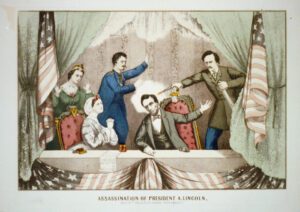

We’ve all seen various lithographic recreations of Lincoln’s assassination. We know the stories related to the fates of the President, the First Lady, and John Wilkes Booth. What about the other two people in the image?

Future Brevet Colonel Henry Rathbone (1837-1911) and his fiancé Clara Harris had known each other for 15 years. Henry’s widowed mother had married Clara’s widowed father, so they were stepsiblings who met at ages 11 and 14 and became close friends. Both families were prominent, with Henry’s father in 1845 leaving him $6.3 m in today’s dollars. Clara’s father was a U.S. Senator from NY.

During the play, noted stage actor John Wilkes Booth entered the presidential box and shot President Lincoln in the back of the head with a pistol. Rathbone heard the shot and turned to see Booth standing in gunsmoke less than four feet behind Lincoln. Rathbone immediately leaped from his seat and grabbed Booth. Rathbone was horrified at the anger on Booth’s face as Booth wrestled himself away, dropped the pistol, drew a dagger, and attempted to stab Rathbone in the chest. Rathbone parried the blow by raising his arms, and Booth slashed Rathbone’s left arm from the elbow to his shoulder.

Although wounded, Rathbone recovered and grabbed onto Booth’s coat as Booth prepared to jump from the box, causing Booth to lose balance as he leaped to the stage. As Booth landed on the stage, Rathbone cried, “Stop that man!” Audience member Joseph B. Stewart climbed over the orchestra pit and footlights and pursued Booth across the stage, repeating Rathbone’s cry of “Stop that man!” several times. Booth escaped and remained at large for twelve days.

Rathbone assessed the President as unconscious and mortally wounded. He rushed to the door of the box to call medical aid. Rathbone testified it was “barred by a heavy piece of plank, one end of which was secured in the wall, and the other resting against the door. It had been so securely fastened that it required considerable force to remove it. This wedge or bar was about four feet from the floor. People outside were beating against the door to enter. I removed the bar, and the door was opened—several persons who represented themselves as surgeons were allowed to enter.

I saw Colonel Crawford there and requested that he prevent others from entering the box. I returned to the box and found the surgeons examining the President’s person. They had not yet discovered the wound. As soon as it was discovered, it was determined to remove him from the theater.”[19] As Lincoln was carried out, Rathbone escorted Mary Lincoln to the Petersen House across the street, where the president was taken. Rathbone said that upon “reaching the head of the stairs, I requested Major Potter to aid me in assisting Mrs. Lincoln across the street to the house where the President was being conveyed.”

Shortly after that, Rathbone passed out due to blood loss. Harris arrived soon after and held Rathbone’s head in her lap while he lay semiconscious. When surgeon Charles Leale, who had been attending Lincoln, finally examined Rathbone, it was realized that his wound was more serious than initially thought. Booth had cut him nearly to the bone and severed an artery. Rathbone was taken home while Harris remained with Mary Lincoln as the president lay in an unconscious state over the next nine hours before he died on the morning of April 15. Genealogist.

The couple married about 15 months after the tragedy of the assassination. Although Rathbone’s physical wounds healed, his mental state deteriorated in the years following Lincoln’s death as he anguished over his perceived inability to thwart the assassination.

After he resigned from the military in 1870, Rathbone struggled to find and keep a job due to his mental instability. He became convinced that Harris was unfaithful and resented the attention she paid to their three children. He reportedly threatened her on several occasions after suspecting that she was going to divorce him and take the children. During this time, he made multiple unsuccessful attempts to obtain a position as a United States consul before eventually being offered the appointment as Consul to Hanover, Germany, by President Chester A. Arthur.

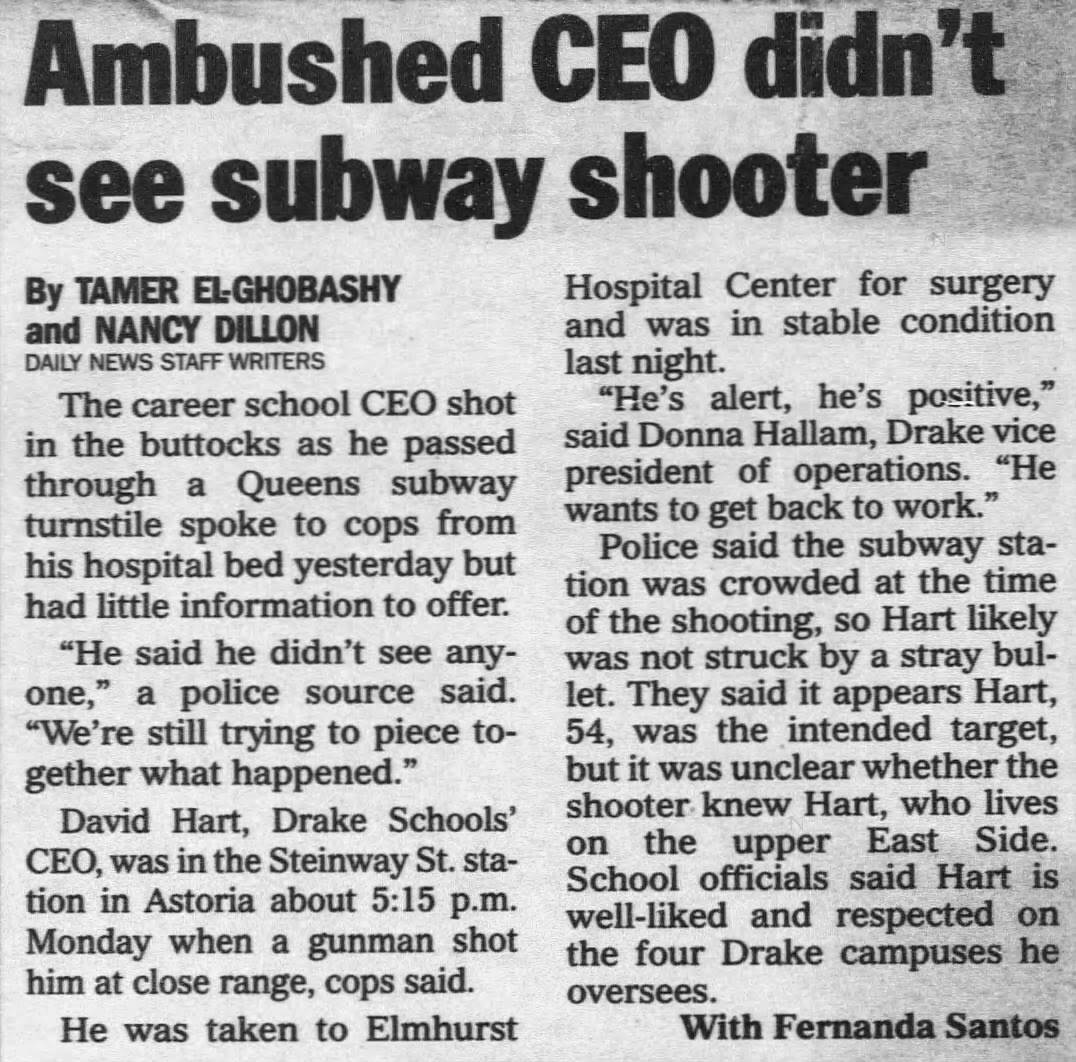

Rathbone and his family relocated to Germany, where his mental health continued to decline. On December 23, 1883, he attacked his children in a fit of madness. He fatally shot and stabbed Clara, who was attempting to protect the children. He stabbed himself five times in the chest in an attempted suicide. He was charged with murder but was declared insane by doctors after he blamed the murder on an intruder. He was convicted and committed to an asylum for the criminally insane in Hildesheim, Germany. The couple’s children were sent to live with their uncle, William Harris, in the United States.

Rathbone spent the rest of his life in the asylum. On August 31, 1910, it was reported that he was “near death”. He died on August 14, 1911, and was buried next to his wife at the Stadtfriedhof Engesohde cemetery in Hanover, Germany.

GENEALOGIST- COUSIN LANCELOT

GENEALOGIST- COUSIN LANCELOT

In the last edition, we covered my ancestor James Clinton Neill’s role in the Alamo and Texas Independence. Here is another relative’s role. Colonel Neill

Lancelot Smither, my first cousin, five times removed, came to Texas from Alabama in 1828 and was granted a league of land on the Brazos River in Austin’s colony, but he never farmed the land.

He spent most of his time in San Antonio de Béxar, trading horses and acting as an unofficial doctor for the Mexican garrison stationed there. In September 1835, Smither accompanied the Mexican force under Lt. Francisco de Castañeda to Gonzales, where he acted as an emissary between the Mexican force and the townsmen in the Mexicans’ attempt to lay claim to the Gonzales “come and take it” cannon. In the course of the negotiations, Smither was taken prisoner by the Texan commander, Col. John H. Moore, and was not permitted to return to the Mexican camp.

After the fight for the cannon, Smither remained in Gonzales. He accompanied the Texas force under Stephen F. Austin on its march from Gonzales to Bexar but was ordered back to Gonzales to repair damage to the home of Ezekiel William incurred during the fighting. On November 2, 1835, Smither was severely beaten by a group of volunteers who passed through Gonzales, robbing houses and terrorizing the town. He was trying to aid Susanna W. Dickinson, who had been driven from her home by the vandals. One month later, the provisional government of Texas authorized payment of $270 to Smither to cover property lost to Castañeda and the vandals at Gonzales. Genealogist.

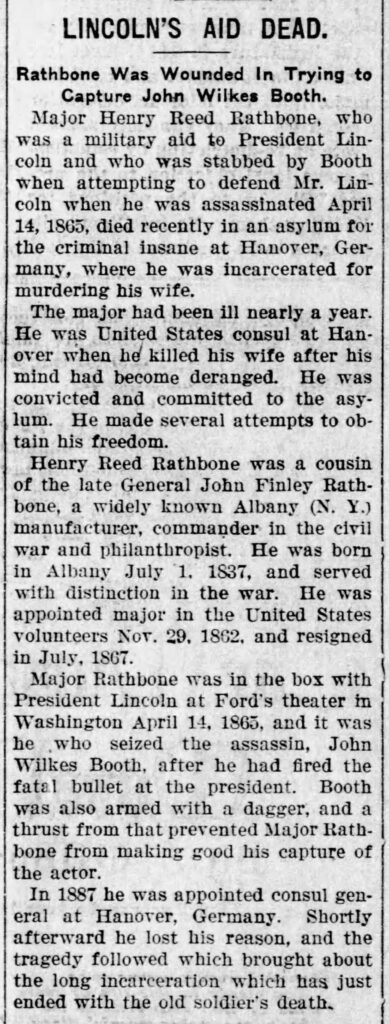

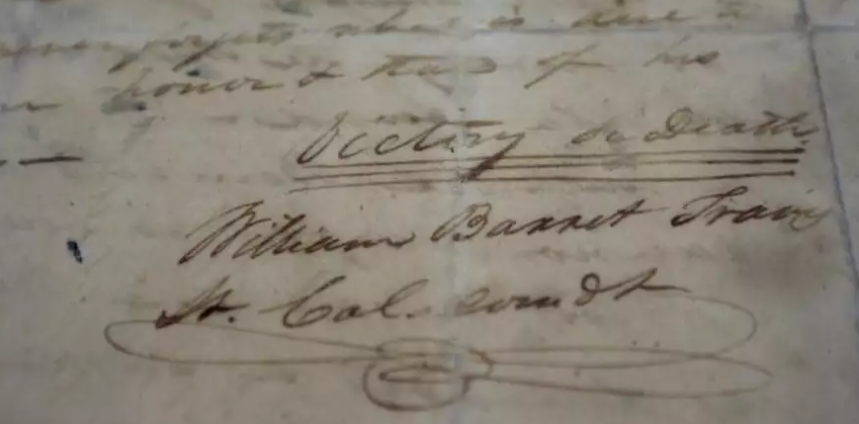

Smither returned to Bexar sometime before the siege of the Alamo. At about 4:00 P.M. on February 23, 1836, he left Bexar for Gonzales to spread the word of the Mexican army’s arrival: the next day, Capt. Albert Martin passed William B. Travis’s famous “Victory or Death” letter (pictured) addressed “to the People of Texas and all Americans in the World” to Smither at Gonzales. Smither added his note to the letter and carried the message to San Felipe.

In 1839–40, Smither served as the city treasurer of San Antonio. From August 19 to September 7, 1841, he served as mayor pro tem during the absence of Mayor Juan N. Seguín. Smither was killed in September 1842, with two others at Sutherland Springs, by Mexican troops under Adrián Woll.

GENEALOGIST- A TONY AND TONY STORY FROM ONE OF OUR CLIENTS

GENEALOGIST- A TONY AND TONY STORY FROM ONE OF OUR CLIENTS

My mother Mary’s Tony Bennett Story

So, the story goes like this:

We all know my mom had a great voice and even earned in high school a scholarship to the Juilliard School of Music. She didn’t take the scholarship for obvious health reasons, etc. But we also know that she loved to sing. Locally, Mary sang on Buffalo’s supper club circuit with her good friend Tony Scibetta (pictured), who played piano. This would have been around the early 1940s. Mary and Tony had been friends for many years.

Well, in the early 1960s, Tony Scibetta made it big time. He started arranging and writing music for Robert Goulet and Ella Fitzgerald and then, shortly after, for Tony Bennett.

Whenever Tony Scibetta returned home to Buffalo, he would always stop by to say “hi” to my mom. Well, one early summer day when Tony was en route from New York City to California, he stopped in Buffalo. First, I’m told to take care of some real estate matters. So, he stopped at our house at 24 Dartmouth to say “hi” and yelled from the driveway, “Hey, Mary, it’s Tony.” My mom yelled to Tony, “Come on in.” (Because she wore a brace and couldn’t always get to the door that easily, friends always knew to yell or ring the doorbell.) When Tony came into the house, who did he have besides the famous singer Tony Bennett?

They were both traveling to California together. My mom was almost in tears and immediately told both Tonys to go to the piano in the living room. She then had Tony Scibetta play the famous hit song “I Left My Heart In San Francisco,” and she had Tony Bennett sing it for her. Quite an experience and a once-in-a-lifetime happening! This was around 1964. It’s a true story and has a happy ending. Genealogist.

GENEALOGIST- THE DONUT STORIES

GENEALOGIST- THE DONUT STORIES

My wife had five Franklin great-uncles who served in the US Navy during WW2. The oldest, Benjamin Santarelli, stayed in the Navy and served in the Adjutant General’s office in Washington, D.C. The youngest, Richard Byron, was a painter who also lived in Washington, DC.

The middle three were all assigned as bakers on Navy ships. Samuel Glass took a propellor to the stomach but survived and never had his digestion working quite right. Lawrence Haworth owned donut shops in the Detroit area, and Stacy Byron also owned donut shops all over the U.S. Stacy was married four times and on the move. He owned an early-day RV.

Stacy built a donut-making machine that I was told he sold to Winchell’s, a familiar chain on the West Coast, where I heard the story. Later, when I contacted Stacy’s descendants in Michigan, they had always heard that he had sold the machine to Dunkin. Is that because Easterners had no reference to Winchell, or did the Westerners have no reference to Winchell? That’s how sometimes family history stories can get convoluted.

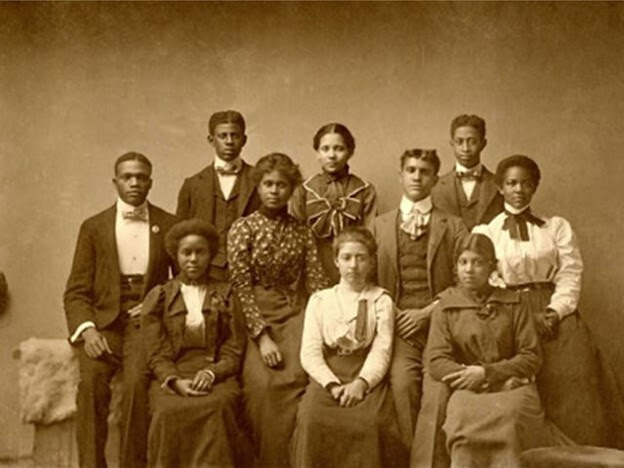

Below are sisters Lucy and Mary with Ben, Haworth, Stacy, Sam, and Richard.

SO, WHAT’S THE REAL STORY- PART II

SO, WHAT’S THE REAL STORY- PART II

One of our client’s cousins had documented in his family history that frontiersman Daniel Boone was a family friend and stayed with members of the Blaise family in Murphysboro, IL, several times.

I pointed out to the client that Daniel Boone died in 1820, and Jean Nicole Blaise was not in America until 1842, so I don’t believe the famous Daniel Boone would have visited the Blaise family in Murphysboro.

However, I found a story about William Boone, an earlier settler in Jackson Co., IL., who was purportedly a brother of Daniel Boone or a relative of Daniel Boone. It mentions that William Boone had a grandson named Daniel Boone. I traced it back, and this Daniel Boone would be the first cousin, four times removed from the famous Daniel Boone. Their common ancestor was George Boone III, the immigrant (pictured). Genealogist.

I also have these Daniel Boone stories and connections in my family. Unfortunately, most did not add up when I looked at the facts. At least a dozen families claim the guy walking next to Daniel Boone in George Caleb Bingham’s Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers through the Cumberland Gap (1851–52) is their ancestor (see below).

The odds are that it was just a guy painted to match the artist George Caleb Bingham’s imagination, as he was just 9 years old when Boone died, so it is not like Bingham was there or asked Boone about the crossing. Bingham had a mentor, Chester Harding, who painted the only live-sitting portrait of Daniel Boone in 1820, so I guess he could have passed his interpretation of the crossing to Bingham that way.

The client still wanted the story in his book, so we called it a “legend”.

GENEALOGIST CHARLOTTE DUPUY VS. HENRY CLAY

GENEALOGIST CHARLOTTE DUPUY VS. HENRY CLAY

Charlotte Dupuy was born into slavery in Cambridge, Maryland. The tailor James Condon brought her to Kentucky in 1805, who had purchased her as a child from Daniel Parker in Cambridge. She was said to have been born about 1787. In about 1806, she met and married Aaron Dupuy (pictured), a young man held by Henry Clay on his Ashland plantation in Lexington, Kentucky. In our last edition, we reported on Henry Clay and Ashland- HENRY CLAY

Condon sold Charlotte to Henry Clay in May 1806, perhaps to allow the young couple to live together. They had two children together.

Clay went to Washington, D.C., for his congressional term beginning in 1810 and took the Dupuys with him. They lived with Clay and served in the house he rented (pictured), initially built for Commodore Stephen Decatur, hero of the War of 1812. Located at Lafayette Square across from the White House today, the Decatur House is a museum and a designated National Historic Landmark.

Charlotte Dupuy and her family enjoyed the relative freedom of living in Washington, D.C., where they met other enslaved people and joined in some of the city’s activities. Clay allowed Charlotte Dupuy to visit her mother and family on the Eastern Shore. Following his Congressional career, Henry Clay served as Secretary of State from 1825 to 1829.

As Clay began making preparations in 1829 to leave the capital when his service ended, Dupuy filed a petition for her freedom and that of her children. She based this on her mother’s freedom and her previous enslaver, Condon, who promised to free her and her children. Clay thought his political enemies had persuaded her to do it and decided to fight, as he was embarrassed by the publicity.

On February 13, 1829, her attorney, Robert Beale, wrote a petition on her behalf to the judges of the District of Columbia. The petition asked the courts to use their power to keep Clay from removing Charlotte Dupuy from the District of Columbia while her lawsuit for freedom was underway. The Court granted this petition.

Beale argued that Dupuy and her children were “entitled to their freedom” based on a promise by her previous enslaver, James Condon, but was “now held in a state of slavery by one Henry Clay (Secretary of State) contrary to the law and your petitioners just rights”. Clay wanted to remove the Dupuys from their DC residence and return them to Kentucky. There, Beale argued, they would “be held as slaves for life”. While the Court allowed Charlotte Dupuy to stay in Washington while the case was heard, it permitted Clay to take her husband Aaron and children Mary Ann and Charles back to Kentucky. Genealogist.

Charlotte Dupuy’s petition to stay in the District temporarily was granted, but her writ for freedom was denied. Clay’s attorney showed that her mother had been freed after Charlotte was born, which did not affect her status as enslaved. Her case was taken seriously because, according to a letter by Henry Clay, Dupuy stayed in DC “upwards of 18 months” after he left for Kentucky, awaiting the trial results. During these 18 months, Clay described her as acting as “her own mistress”.

Dupuy worked for wages for the succeeding Secretary of State, Martin Van Buren, who also lived at Decatur House. The letter shows that Dupuy never willingly left DC. On the first page, Clay mused, “How shall I now get her …?” He approved of his agent’s having Dupuy arrested when she refused to return to Kentucky.

Although Dupuy was fighting for her freedom, the courts, to hear her case, had to assume her status as a free negro or a free person of color since enslaved people had no legal standing in the courts. Such actions began to create political space for enslaved people’s freedom. The Court determined that the agreement between Dupuy and Condon did not apply to any new enslavement and rejected her claim against Clay.

Clay’s agent arranged for Dupuy to be imprisoned in Alexandria, which was then part of the District of Columbia, while he decided what to do. Clay had Dupuy removed from Washington and transported to New Orleans, to the home of his daughter and son-in-law Martin Duralde. She was enslaved there for another decade.

Finally, on October 12, 1840, Henry Clay freed Charlotte Dupuy and her daughter Mary Ann in New Orleans. He retained her son Charles Dupuy, who traveled with him to speaking engagements. Clay frequently used him as an example of how well he treated enslaved people. He eventually freed Charles in 1844.

Clay, either before he died in 1852 or by his will, or his descendants, freed Charlotte’s husband Aaron Dupuy or “gave him his time”. The couple reunited to live again in Kentucky, where Aaron worked for John M. Clay at Ashland after his father’s death. While no deed of emancipation was found for Aaron Dupuy, according to the 1860 census, he and Charlotte Dupuy lived together as free persons in Fayette County, Kentucky. An obituary of Aaron Dupuy said he died February 6, 1866, and was survived by his widow, although she was not listed by name.

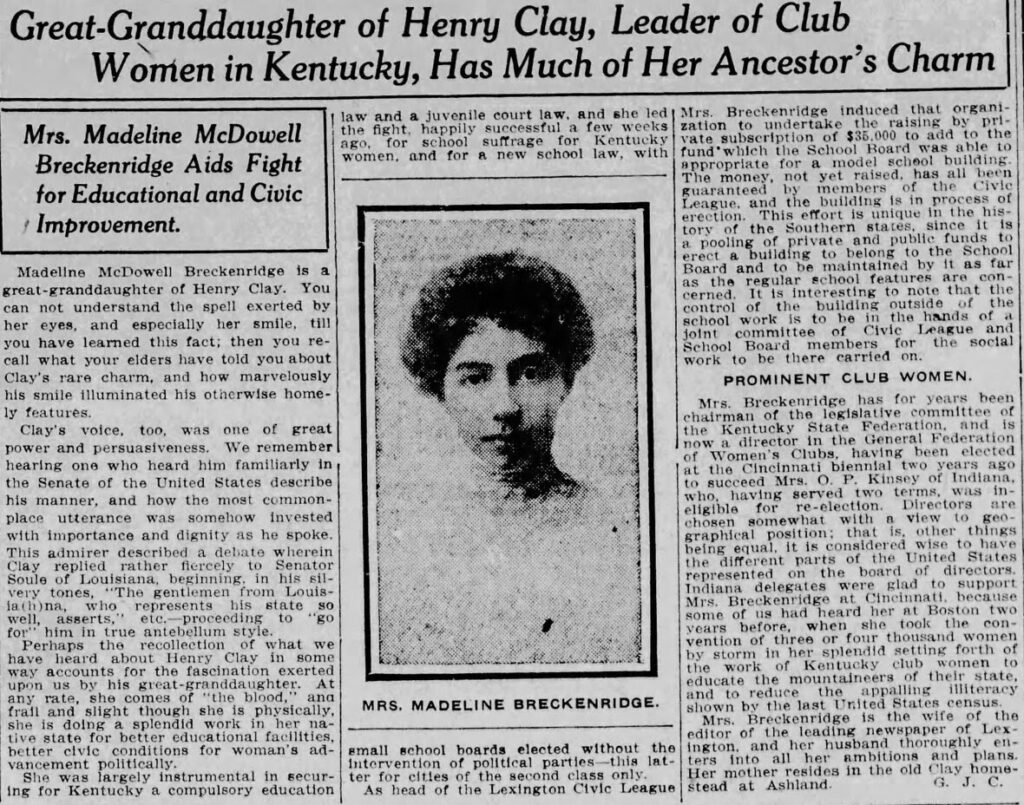

GENEALOGIST HENRY CLAY’S SUFFRAGETTE GREAT GRANDAUGHTER

GENEALOGIST HENRY CLAY’S SUFFRAGETTE GREAT GRANDAUGHTER

Madeline (Madge) McDowell Breckinridge (1872 – 1920) grew up at Ashland, the farm established by her great-grandfather, nineteenth-century statesman Henry Clay. Her mother was Henry Clay, Jr.’s daughter, Anne Clay McDowell, and her father was Major Henry Clay McDowell (a namesake of Henry Clay), who served during the American Civil War on the Union side. They purchased the Ashland estate in 1882.

Her brother Thomas was a renowned thoroughbred racehorse owner, breeder, and trainer who won the 1902 Kentucky Derby. In our last edition, we covered Henry and Thomas HENRY CLAY AND ASHLAND

Madeline was educated in Lexington, Kentucky, at Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut, and at State College (now the University of Kentucky) between 1890 and 1894. She suffered from illness during her college years and, due to tuberculosis of the bone, part of one leg was amputated, and she received a wooden leg.

The once athletic young woman became more studious. She wrote book reviews for the Lexington Herald and studied German philosophy and literature with other Fortnightly Club members.

On November 17, 1898, Madeline McDowell married Desha Breckinridge, the editor of the Lexington Herald and the great-grandson of presidential candidate John Breckenridge, who was discussed in the article in the same edition on “Preventing the Civil War”.

The Breckinridge’s together used the newspaper’s editorial pages to promote political and social causes of the Progressive Era, especially programs for the poor, child welfare, and women’s rights. During their marriage, Desha was not a faithful man, so Breckinridge escaped her embarrassment by being busy with her civic activities. She was a patient in a Denver, Colorado, sanitarium in 1903 and 1904. About 1904, when she was 32 years of age, she suffered a stroke. Genealogist.

She lived to see the women of Kentucky vote for the first time in the 1920 presidential election. She also initiated progressive reforms for compulsory school attendance and child labor. She founded many civic organizations, notably the Kentucky Association for the Prevention and Treatment of Tuberculosis. She led efforts to implement model schools for children and adults, parks and recreation facilities, and manual training programs.

In their book, A New History of Kentucky, Lowell H. Harrison and James C. Klotter state that Breckinridge was the most influential woman in the state. She was named one of the Kentucky Women Remembered in 1996, and her portrait is permanently displayed at the state capitol (pictured). She was “regarded by some as militant, was one of Kentucky’s most active suffragists and a fervent supporter of the Nineteenth Amendment.”

FOREIGN VISITORS SPENDING THE NIGHT IN RURAL AMERICA

FOREIGN VISITORS SPENDING THE NIGHT IN RURAL AMERICA

My mother-in-law’s first cousin, Marian, shared a story with me:

In the 1950s, they sponsored two foreign exchange students from Africa. Part of their experience was a trip across the U.S., where they spent the night with host families that Marian had been involved with arranging.

One of those nights was in Midland, TX.

Marian says she had wondered if those two boys, later back in Africa, ever realized that they spent the night at the home of two future U.S. Presidents.

Pictured is the George H.W. and George W. Bush home in Midland.

GENEALOGIST WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS KNOWING ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

GENEALOGIST WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS KNOWING ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

Reach out to Dancestors Genealogy. Our genealogists will research, discover, and preserve your family history. No one is getting any younger, and stories disappear from memory every year and eventually from our potential ability to find them.

Preserve your legacy and the heritage of your ancestors.

Paper gets thrown in the trash; books survive!

Ready to embark on your family history journey? Don’t hesitate. Call us at 214-914-3598, and let’s get your project started! Genealogist.

GENEALOGIST- ONE KILLING LEADS TO ANOTHER 20 YEARS LATER

GENEALOGIST- ONE KILLING LEADS TO ANOTHER 20 YEARS LATER GENEALOGIST- COUSIN LANCELOT

GENEALOGIST- COUSIN LANCELOT GENEALOGIST- A TONY AND TONY STORY FROM ONE OF OUR CLIENTS

GENEALOGIST- A TONY AND TONY STORY FROM ONE OF OUR CLIENTS GENEALOGIST- THE DONUT STORIES

GENEALOGIST- THE DONUT STORIES SO, WHAT’S THE REAL STORY- PART II

SO, WHAT’S THE REAL STORY- PART II GENEALOGIST CHARLOTTE DUPUY VS. HENRY CLAY

GENEALOGIST CHARLOTTE DUPUY VS. HENRY CLAY GENEALOGIST HENRY CLAY’S SUFFRAGETTE GREAT GRANDAUGHTER

GENEALOGIST HENRY CLAY’S SUFFRAGETTE GREAT GRANDAUGHTER FOREIGN VISITORS SPENDING THE NIGHT IN RURAL AMERICA

FOREIGN VISITORS SPENDING THE NIGHT IN RURAL AMERICA GENEALOGIST WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS KNOWING ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

GENEALOGIST WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS KNOWING ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?