08 Sep Genealogy Newsletter- September 9, 2023

Contents

- 1 GENEALOGY- WAS DR. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN ANOTHER SWEENEY TODD?

- 2 GENEALOGY- BEFORE THERE WAS STARBUCKS IN A BAG THERE WAS ROWNTREES IN A CAN

- 3 GENEALOGY- DID YOU KNOW FOLGERS AND STARBUCKS HAD MERGED?

- 4 GENEALOGY- CONTINUING WITH SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OR THE CONSTITUTION

- 5 GENEALOGY- MORE GRUEL,DADDY?

- 6 GENEALOGY- WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

GENEALOGY- WAS DR. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN ANOTHER SWEENEY TODD?

GENEALOGY- WAS DR. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN ANOTHER SWEENEY TODD?

We visited Ben Franklin’s house in London, as I am working on a Franklin genealogy. The only residence of his that is still remaining. It is worth the visit.

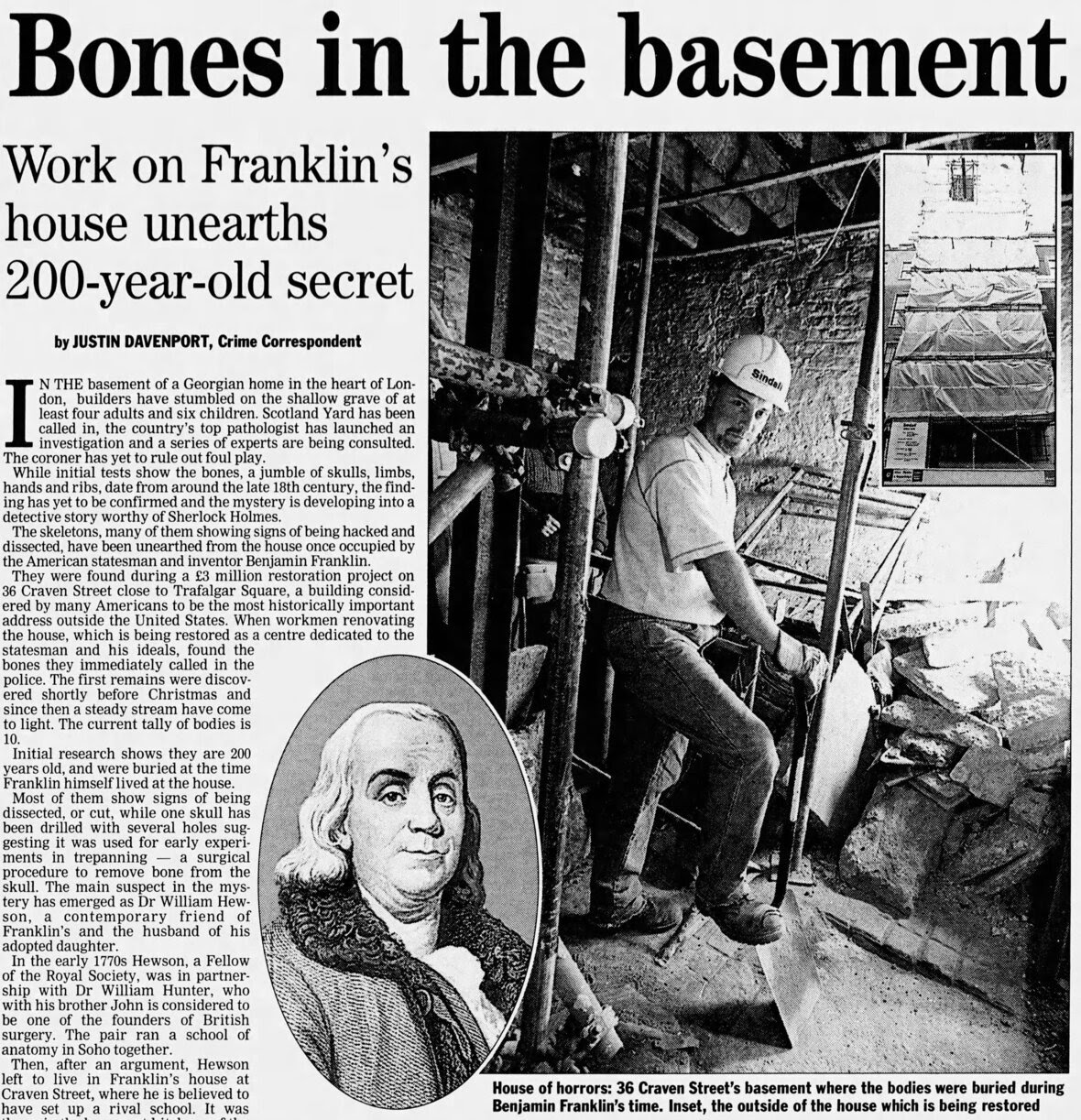

When the Friends of Ben Franklin House, started the restoration, the workmen discovered the bones of ten people buried onsite.

After wondering about what Old Ben might have been up to we found about another tenant in the house.

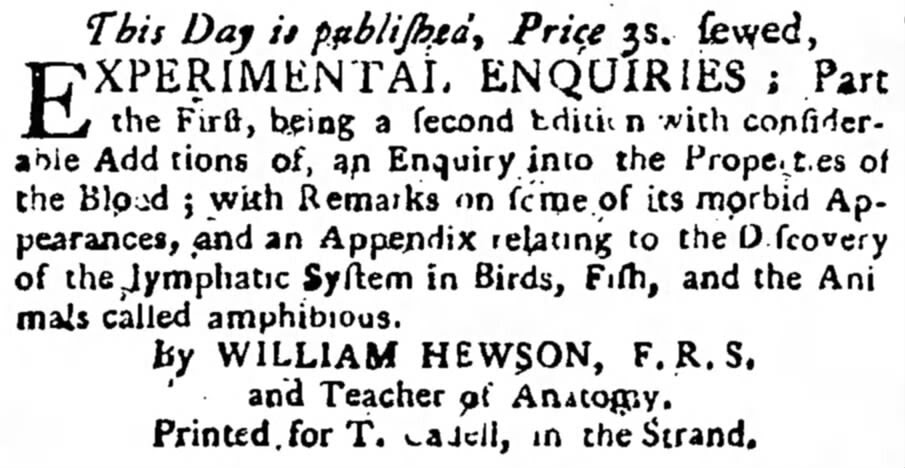

William Hewson (pictured above) was elected to the American Philosophical Society, awarded the Copley Medal in 1769, and was elected to the Royal Society in 1770.

His significant contribution was isolating fibrin, an essential protein in the blood coagulation. His Copley work came when he showed the existence of lymph vessels in animals and explained their function by hypothesizing the presence of a human lymphatic system. He also demonstrated that red blood cells were discoid rather than spherical, as had been previously supposed by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, but incorrectly identified the cells’ dark centers as their nuclei. In 1773, he produced evidence for the concept of a cell membrane in red blood cells – however, this last work was largely ignored.

On July 10, 1770, he married Mary Stevenson (better known as Polly), a London friend and the landlady of Benjamin Franklin. From September 1772, he ran an anatomy school at 36 Craven Street, where Franklin lodged in London.

In 1998, workers restoring the London home (Benjamin Franklin House) dug up the remains of six children and four adults hidden below the home. The Times reported on February 11, 1998:

Initial estimates are that the bones are about 200 years old and were buried when Franklin lived in the house, which was his home from 1757 to 1762 and from 1764 to 1775. Most bones show signs of being dissected, sawn, or cut. One skull has been drilled with several holes. Paul Knapman, the Westminster Coroner, said yesterday: “I cannot discount the possibility of a crime. There is still a possibility that I may have to hold an inquest.”

The Friends of Benjamin Franklin House (the organization responsible for restoring Franklin’s house at 36 Craven Street in London) note that the bones were likely placed there by Hewson, who lived in the house for two years. They note that Franklin likely knew what Hewson was doing. Archaeological evidence demonstrated proof, which showed liquid mercury associated with turtle bones and vermilion coloring associated with dog bones found in the deposit. Hewson had documented experimentation on the lymphatic system using both substances and animals.

It seems 36 Craven Street was the perfect place for an anatomy school: Hewson was married to the landlady’s daughter; the tenant, Ben Franklin, was a trusted friend; and the house lay between two sources of material.

Resurrectionists could smuggle bodies from graveyards via the Thames-side wharf at the end of the street, or snaffle unfortunate cadavers from the gallows at the other.

The Friends of Benjamin Franklin House suggest that Hewson probably used bodies from ‘resurrectionists – bodysnatchers who shipped their wares along the Thames under cover of night.’

Not only were uncertified dissections illegal, the means by which Hewson gained his materials were also against the law; disposing of these bones somewhere other than the basement would have risked being prosecuted for illegal dissection and possible grave robbing.

Ironically, Hewson died on May 1, 1774, due to sepsis contracted while dissecting a cadaver.

As part of his last will and testament (1789), Benjamin Franklin made the following bequest: To my dear old friend, Mrs. Mary Hewson, I give one of my silver tankards marked for her use during her life, and after her decease, I give it to her daughter Eliza. I give to her son, William Hewson, who is my godson, my new quarto Bible, and also the botanic description of the plants in the Emperor’s garden at Vienna, in folio, with colored cuts. And to her son, Thomas Hewson, I give a set of “Spectators, Tattlers, and Guardians” handsomely bound.

Read more at https://londonist.com/2016/05/the-bones-in-benjamin-franklins-basement

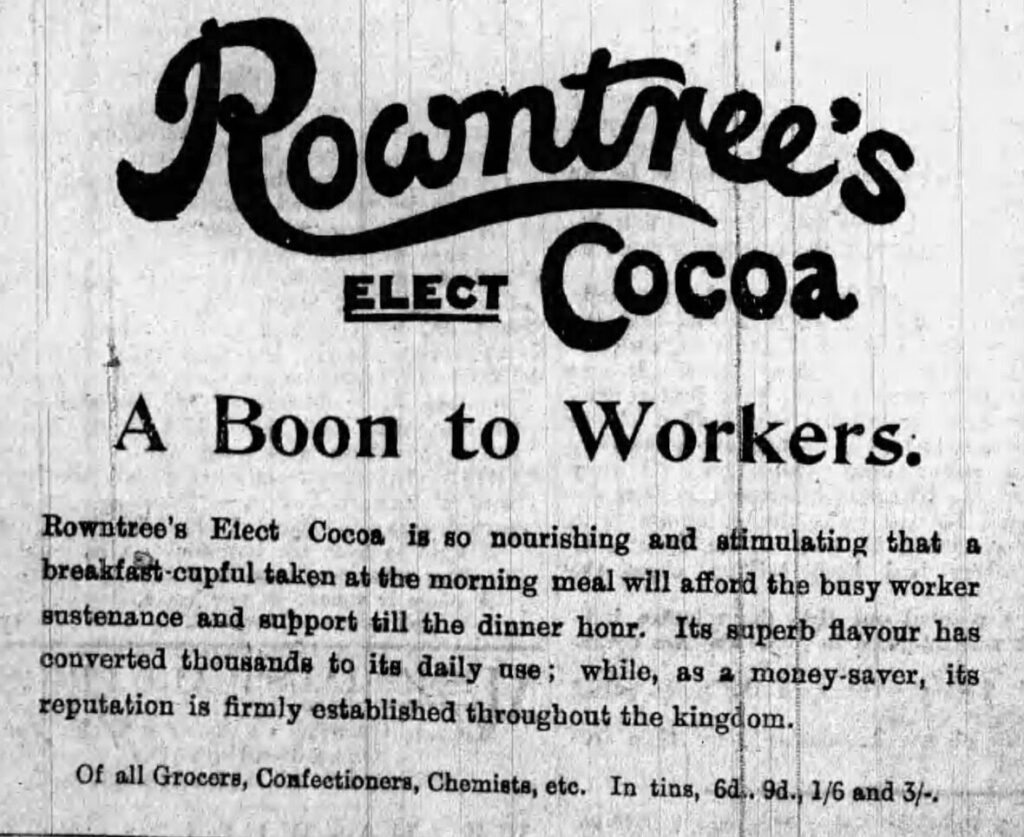

GENEALOGY- BEFORE THERE WAS STARBUCKS IN A BAG THERE WAS ROWNTREES IN A CAN

GENEALOGY- BEFORE THERE WAS STARBUCKS IN A BAG THERE WAS ROWNTREES IN A CAN

Founded in 1862, the company developed strong associations with Quaker philanthropy. Throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries, it was one of the big three confectionery manufacturers in the United Kingdom, alongside Cadbury and Fry, founded by Quakers.

Rowntree’s was founded in 1862 at Castlegate, in York, by Henry Isaac Rowntree, a Quaker, as the company manager bought out the Tuke family.

In 1864, Rowntree acquired an old iron foundry at Tanners Moat and moved production there. By 1869, Rowntree was in financial difficulties, and his brother, Joseph Rowntree, joined him in full partnership, and H.I. Rowntree & Co was formally established.

Joseph pursued his progressive ideas within the running of Rowntree’s, in the design of the new factory opened in 1881, and in the business practices followed therein. He provided his employees with a library, free education, a works magazine, a social welfare officer, a doctor, a dentist, and the founding of one of the first Occupational Pension Funds.

Rowntree’s grew from 30 to over 4,000 employees by the end of the 19th century, making it Britain’s eightieth largest manufacturing employer. It merged with John Mackintosh and Co. in 1969 and was taken over by Nestlé in 1988.

Taking the genealogy, a bit further, Joseph’s legacy of progressiveness came from his father. Joseph Sr. (1801-1859) was an English shopkeeper and educationalist. Rowntree was born in Scarborough, North Yorkshire, England, the son of the Quakers John Rowntree (1757–1827) and his wife, Elizabeth Lotherington (1764–1835). By age 13, he was assisting his father and brother John in the grocery business on Bland’s Cliff, which his father had established.

In 1822, he started a grocery shop in York, eventually becoming a master grocer. The business prospered, and in 1845, the family moved to Blossom Street, then, in 1848, to 39 Bootham, York. During the 1850s, his two elder sons became partners in the business. Christopher Robinson (not of Winne the Pooh fame) had joined as a manager, and William Hughes was in charge of the apprentices. This gave Joseph the time to channel his energies into a wide range of social and educational issues.

His accomplishments included:

• From 1830 until his death, he was honorary secretary of the Quaker boys and girl’s schools in York

• Establishing a financially sound insurance scheme resulted in the Friends Provident Institution (1832), the introduction of whose Rules and Regulations needed to make clear to Quakers that life insurance neither implied a distrust of Providence nor was like a lottery.

• He impacted the education of Quaker children, the training of male and female teachers, and the education of poor children in York through the British and Foreign School Society.

• He was active in municipal reform in York and became an alderman in 1853.

• Statute law provided that marriages, according to Quaker usage, were valid only if both were Quaker members. In 1856, he persuaded the Yorkshire Meeting to ask the national meeting in London to take steps to end this limitation (a proposal unpopular in more conservative quarters). It was not until 1859 that the Yearly Meeting was prepared to ask Parliament to broaden the provision, and the Marriage (Society of Friends) Act 1860 provided this change.

Here is more on Rowntree: https://www.rowntreesociety.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Exhibition-Book.pdf

GENEALOGY- DID YOU KNOW FOLGERS AND STARBUCKS HAD MERGED?

GENEALOGY- DID YOU KNOW FOLGERS AND STARBUCKS HAD MERGED?

When we were touring Benjamin Franklin’s house in London, we discussed with the curator that Benjamin’s mother was Abiah Folger. Her father, Peter Folger or Foulger (died 1690), was a poet and an interpreter of the American Indian language for the first settlers of Nantucket. He was instrumental in the colonization of Nantucket Island in the Massachusetts colony.

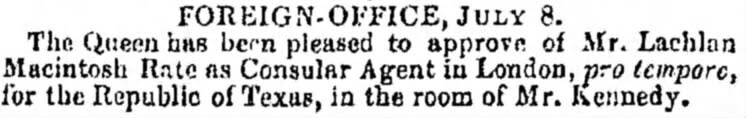

I mentioned that, like the Folgers, my wife’s Starbuck and Coffin ancestors were early founders of Nantucket. The Starbucks and the Coffins began whaling seriously in the 1690s in local waters.

Her ancestor, Captain Hezekiah Starbuck, commanded the first American ship to round Cape Horn. He also commanded a Nantucket whaler, the Beaver, which, after conveying a load of whale oil to England and returning with a cargo of 112 chests of British East India Company tea, was one of three vessels in Boston Harbor (the others were Dartmouth and Eleanor) which had their cargoes dumped overboard during the Boston Tea Party on the night of December 16, 1773. He found his trade significantly disrupted during the Revolutionary War. At the outset of the war, his ship was at sea. When they returned to Nantucket, he found a British man-of-war between them and port. They had to outmaneuver the enemy to get into port. He remained on the island until the war was over.

In 1785, Hezekiah moved his family to the Friends New Garden Meeting (Quaker) in Guilford Co, North Carolina, to join other Starbucks that had moved there before the war. He was also a farmer, surveyor, and an amateur physician. He wrote a fifteen-page pamphlet on treating cancerous afflictions, published in Raleigh, North Carolina 1814.

Before my wife joked about it, I had never thought about the coffee connection between Folger and Starbucks names, so I went to see if there was ever a marriage between the two Nantucket families. Genealogy records show that Hezekiah’s Great-Great Uncle Nathaniel Starbuck became Nantucket’s first millionaire as a whaler and mercantilist. He married Dinah Coffin (one of many marriages among the two families). Their daughter Mary Starbuck married Jethro Folger, Peter Folger’s grandson and Benjamin Franklin’s first cousin, on December 9, 1710, in Nantucket, the Folgers and Starbucks merger date.

GENEALOGY- CONTINUING WITH SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OR THE CONSTITUTION

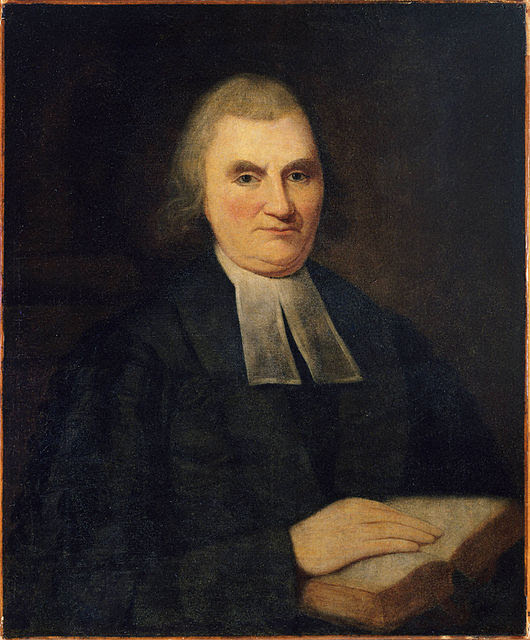

John Witherspoon (February 5, 1723 – November 15, 1794) was a Scottish-American Presbyterian minister, educator, farmer, slaveholder, and a Founding Father of the United States. Witherspoon embraced the concepts of Scottish common- sense realism, and while president of the College of New Jersey (1768–1794; now Princeton University) became an influential figure in the development of the United States’ national character. Politically active, Witherspoon was a delegate from New Jersey to the Second Continental Congress and a signatory to the July 4, 1776, Declaration of Independence. He was the only active clergyman and the only college president to sign the Declaration. Later, he signed the Articles of Confederation and supported ratification of the Constitution of the United States.

Witherspoon was a staunch Protestant, nationalist, and supporter of republicanism. Consequently, he was opposed to the Roman Catholic Legitimist Jacobite rising of 1745–46. Following the Jacobite victory at the Battle of Falkirk, he was briefly imprisoned at Doune Castle (which we visited earlier this week), which had a long-term effect on his health.

At the urging of Benjamin Rush and Richard Stockton, whom he met in Paisley, Witherspoon finally accepted their renewed invitation (having turned one down in 1766) to become president and head professor at the small Presbyterian College of New Jersey in Princeton. Thus, Witherspoon and his family emigrated to New Jersey in 1768.

At the age of 45, he became the sixth president of the college, later known as Princeton University. Upon his arrival, Witherspoon found the school in debt, with weak instruction, and a library collection which clearly failed to meet student needs. He immediately began fund-raising—locally and back home in Scotland—added three hundred of his own books to the library, and began purchasing scientific equipment including the Rittenhouse orrery, many maps, and a terrestrial globe. Witherspoon instituted numerous reforms, including modeling the syllabus and university structure after that used at the University of Edinburgh and other Scottish universities. He also firmed up entrance requirements, which helped the school compete with Harvard and Yale for scholars.

GENEALOGY- MORE GRUEL,DADDY?

GENEALOGY- MORE GRUEL,DADDY?

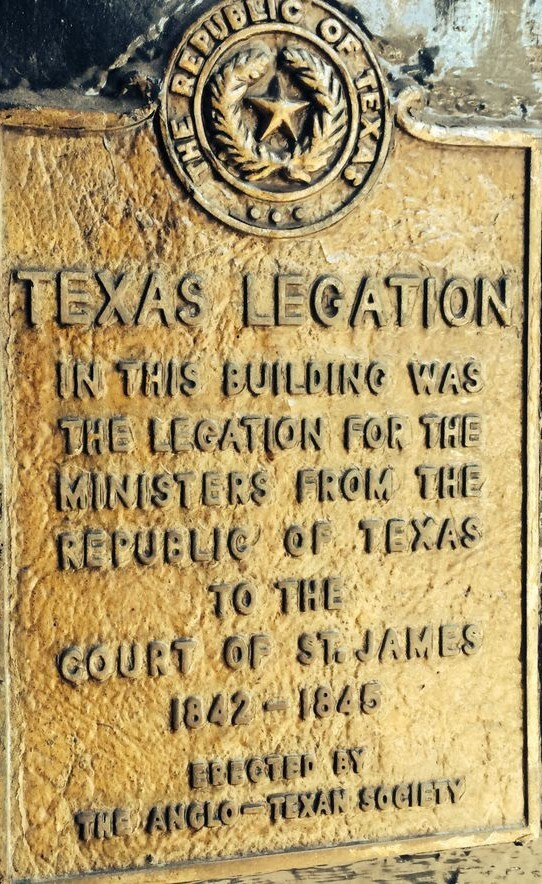

Mary Blandy’s parents raised her as an intelligent, articulate Anglican woman. Her reputation in Henley, where she lived her entire life, was that of a well-respected, well-mannered, and well-educated young woman. In 1746, Mary met Captain William Henry Cranstoun. The two intended to marry in 1751. However, it was exposed that he married a woman in Scotland and had a child by this marriage. Cranstoun denied the validity of this marriage and made several trips to Scotland throughout his relationship with Mary to have the marriage annulled.

After months of stalling, Mary’s father, Francis Blandy, became suspicious of Cranstoun and believed he did not intend to leave his wife. Mr. Blandy did not attempt to hide his disapproval of Cranstoun’s marriage. What happened next is unclear. Mary claimed that Cranstoun sent her a love potion (which later turned out to be arsenic) and asked her to place it in her father’s food to make him approve of their relationship. Mary did this, and her father died.

The March 3, 1752 trial was of some forensic interest, as there was expert testimony about the arsenic poisoning that Dr. Anthony Addington presented. Addington had done testing that would be rudimentary by today’s standards but was quite fascinating in the eighteenth century, based on testing residue for traces of arsenic, to such an extent that Dr. Addington’s career was made. The doctor eventually became the family doctor to William Pitt, Earl of Chatham. His son was Henry Addington, future Prime Minister and Home Secretary (as Viscount Sidmouth).

On Easter Monday, April 6, 1752, Blandy was hanged outside Oxford Castle prison for parricide. Her case attracted a great deal of attention from the press. Many pamphlets claiming to be the “genuine account” or the “genuine letters” of Mary Blandy were published in the months following her execution. The reaction among the press was mixed. While some believed her version of the story, most thought she was lying. The debate over whether or not she was morally culpable for her crime continued for years after her death. In the nineteenth century, her case was re-examined in several texts with a more sympathetic light, and people began to think of her as a “poor lovesick girl”.

GENEALOGY- WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

Reach out to Dancestors to research, discover, and preserve your family history. No one is getting any younger, and stories disappear from memory every year and eventually from our potential ability to find them. Paper gets thrown in the trash; books survive! So do not hesitate and call me @ 214-914-3598.

GENEALOGY- WAS DR. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN ANOTHER SWEENEY TODD?

GENEALOGY- WAS DR. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN ANOTHER SWEENEY TODD?

GENEALOGY- BEFORE THERE WAS STARBUCKS IN A BAG THERE WAS ROWNTREES IN A CAN

GENEALOGY- BEFORE THERE WAS STARBUCKS IN A BAG THERE WAS ROWNTREES IN A CAN GENEALOGY- DID YOU KNOW FOLGERS AND STARBUCKS HAD MERGED?

GENEALOGY- DID YOU KNOW FOLGERS AND STARBUCKS HAD MERGED? GENEALOGY- MORE GRUEL,DADDY?

GENEALOGY- MORE GRUEL,DADDY?