04 Jun Descendants Newsletter- June, 2024

Contents

- 1 COULD YOU GET A PENSION FOR YOUR DESCENDANTS IF YOU HAD A JOB WITH NO SALARY?

- 2 AARON BURR PLAYING CUPID

- 3 THOMAS JEFFERSON AND THE HEMINGS DESCENDANTS

- 4 DESCENDANTS- BETWEEN THIS GUY AND BENEDICT ARNOLD, WE WERE FORTUNATE TO WIN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR

- 5 A REVOLUTIONARY ERA FEMINIST

- 6 THE LAST CIVIL WAR PENSION TO A CIVIL WAR DESCENDANT WAS PAID IN 2020

- 7 WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS?

COULD YOU GET A PENSION FOR YOUR DESCENDANTS IF YOU HAD A JOB WITH NO SALARY?

COULD YOU GET A PENSION FOR YOUR DESCENDANTS IF YOU HAD A JOB WITH NO SALARY?

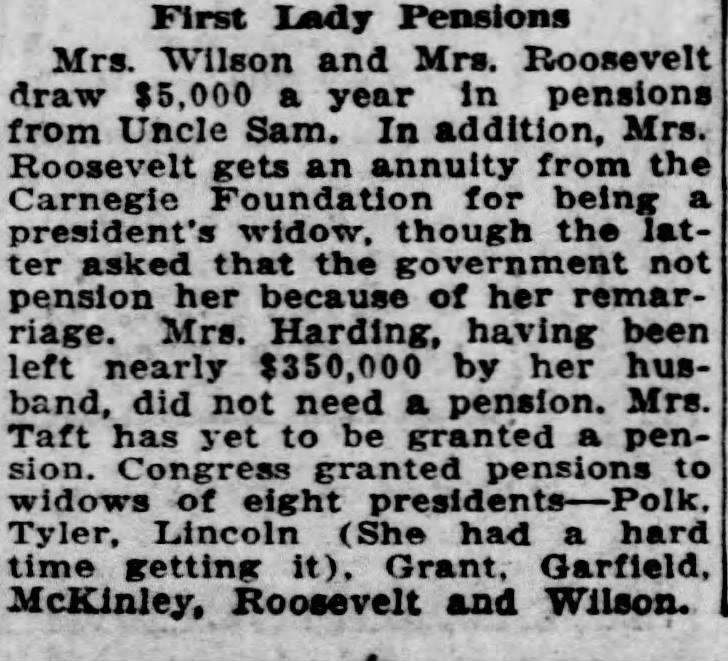

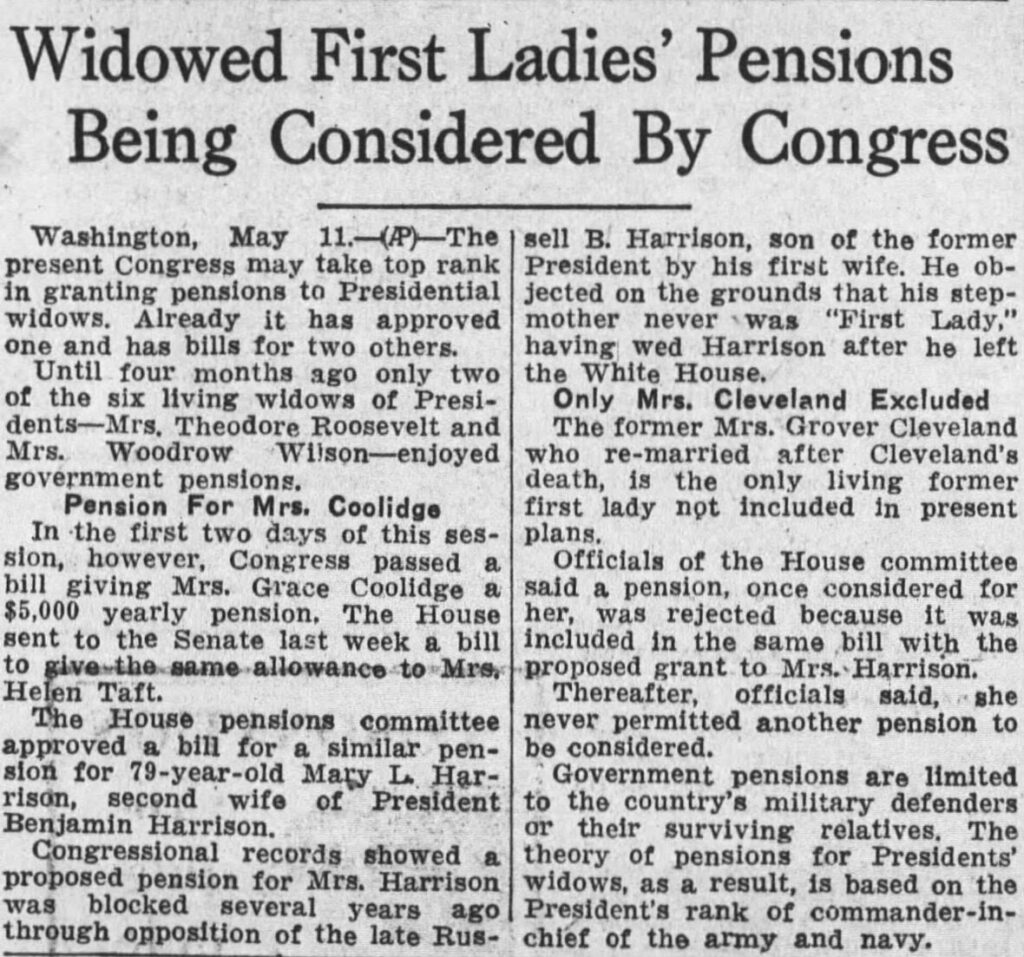

The answer is yes if you are a former First Lady. The president’s wife receives no salary, but they can receive a pension.

I became aware of first ladies’ pensions when we visited Sherwood Forest. The former first lady Julia Gardiner Tyler, known as the “Rose of Long Island”, at 22, married 52-year-old President John Tyler as his second wife and was the first to broach the subject. Tyler served as president from 1841-1845. Julia was known as a grand hostess in the Washington social scene. They retired to Sherwood Forest.

When Virginia left the Union, the Tyler’s became citizens of the Confederacy. Tyler joined the Confederate House of Representatives. He died of a stroke on January 18, 1862, at the age of 71.

Julia hired a manager and two employees to tend to Sherwood Forest Plantation. Then, with her two youngest children, she traveled to Bermuda, where she lived with other Confederates who had settled there, and she returned to her family home in New York in November 1862. She bitterly argued with her Unionist brother, who was eventually banished from the house after striking her. Julia was upset to hear that Sherwood Forest Plantation had been captured while she was in New York, that her former slaves had been given the crops that they grew, and that the building was being used as a desegregated school.

Tyler continued to support the Confederacy throughout the war, making donations to the Confederate Army and distributing pamphlets in support of the cause. The day after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865, three men broke into her home demanding that she turn over her Confederate flag, searching for it after she denied having one. She suspected her brother of orchestrating the attack. The Tyler’s remained unpopular after the war for supporting the Confederacy, so the Tyler children were sent out of the country for schooling.

Julia inherited the Gardiner-Tyler House in Staten Island and three-eighths of the family’s property in New York City. She moved into the Gardiner-Tyler House and lived there until 1874.

Tyler resumed her socialite status in Washington in the 1870s as the stigma of her Confederate sympathies subsided. She sometimes attended White House events, supporting First Lady Julia Grant as a hostess. In 1870, Tyler donated a portrait of herself (above) to the White House, starting the first ladies’ portrait collection.

The economic depression that followed the Panic of 1873 depleted her finances, forcing her to sell her other properties so she could purchase Sherwood Forest Plantation back from the Bank of Virginia that had come to control it. She lobbied Congress for a pension and was granted a monthly allowance in 1880 that amounted to $1800 annually.

Following the assassination of President James Garfield in 1881, Congress granted an annual pension of $5,000 to widows of former presidents. In order of their time in the role after Julia Tyler, these first ladies received a pension: Peggy Taylor, Mary Lincoln, Julia Grant, Anna Harrison, Lucretia Garfield, Ida McKinley, Edith Wilson, Florence Harding, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Jacqueline Kennedy all received pensions.

Nowadays, the “pension precedent” isn’t used as much — the most recent first lady to take advantage of it was Lady Bird Johnson. Currently, being the widow of a former president can get you a $20,000 annual payment. Descendants.

More on Julia Tyler Gardiner on this link:

AARON BURR PLAYING CUPID

AARON BURR PLAYING CUPID

While visiting James Madison’s Montpelier, we learned about a future vice president playing Cupid for a future president.

When Aaron Burr arrived in Philadelphia as the newly elected senator from New York, he faced the same housing shortage that challenged all new members of Congress. There weren’t enough lodgings to go around. He considered himself fortunate to find a place in the boarding house of Mrs. Mary Payne, a Quaker widow, likely sometime in 1793.

One of the attributes of boarding with Mrs. Payne was the presence of her daughter, Dolley Payne Todd (1768-1849). Dolley was soon to be widowed as well, losing both her husband and an infant son in the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793. At twenty-six, Dolley was tall, vivacious, and voluptuous, and she and Burr – who always enjoyed the company of attractive, intelligent women – soon became friends.

Dolley was impressed by Burr and his beliefs regarding the education of his daughters and stepsons. After her husband’s death, she chose Burr to be her surviving son Payne’s legal guardian, noting in her will that “the education of my son is to him and me the most interesting of all earthly concerns.”

One of Burr’s other friends in Philadelphia was James Madison (1751-1836), the well-established and respected representative from Virginia. At 43, Madison was regarded as a confirmed bachelor, and his small stature, shyness, and unprepossessing demeanor were hardly the characteristics of a lady’s man.

Although he was five years older than Burr, the two men had attended the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) at the same time, with the intellectually precocious Burr completing his bachelor’s degree at sixteen. Now Burr and Madison were drawn together as political allies in Congress.

But in the spring of 1794, Madison had a different alliance in mind. He had seen the famously striking Mrs. Todd walking with friends and asked Burr if he would make an introduction. Burr happily obliged, and though no record remains of how exactly he presented his friend’s suit, Mrs. Todd agreed to receive “the great little Madison”, as she called him to a friend. According to family legend, the fashion-conscious Mrs. Todd greeted him wearing a gown of mulberry-colored silk satin. No wonder Madison was instantly smitten and determined to marry her.

Mrs. Todd was likely more pragmatic. Madison was nearly two decades older than she, several inches shorter, and inclined to ill health. But he was wealthy and powerful and would offer security and prestige not only to her but to her son as well.

Still, she didn’t accept Madison right away. In the summer of 1794, she left Philadelphia to avoid the annual fevers that killed her first husband and visited Virginia to visit friends. Undeterred, Madison followed, and by the middle of August, she had agreed to marry him.

Dolley Payne Todd married James Madison on September 15, 1794. Because the wedding was a small family ceremony in Virginia, Aaron Burr was not among the guests. But it’s very likely that when the newlyweds returned to Philadelphia, he was among the first to raise a glass in honor of his two friends, now husband and wife, due partly to his successful matchmaking.

The article was lightly edited from Susan Holloway’s article below, and the image came from the article on the Lost Daguerreotype of James and Dolley Madison.

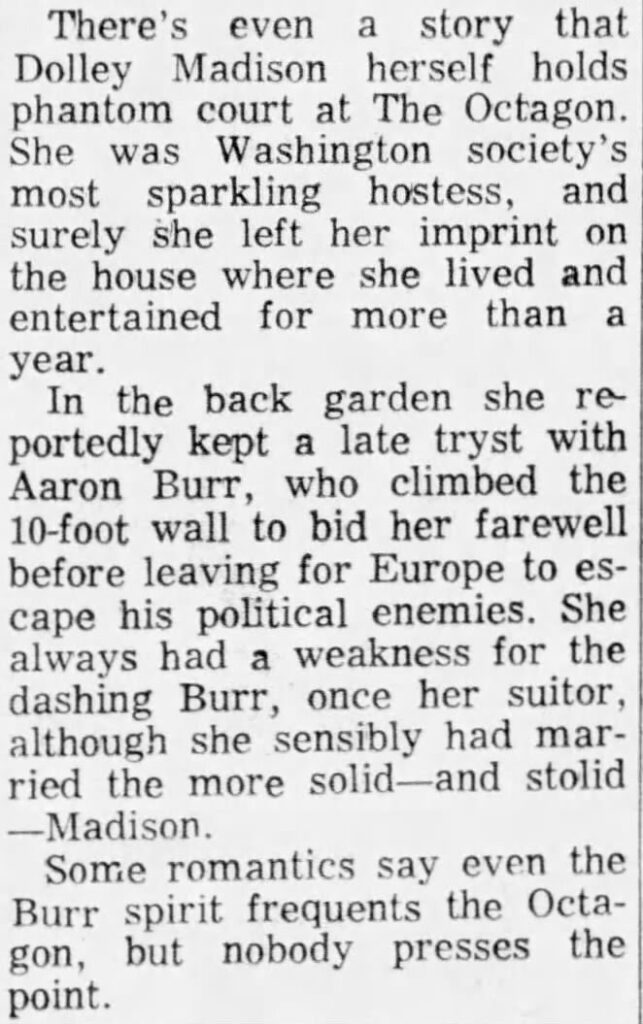

I found an article about Ghosts in the Capital, specifically the house where the Madison’s lived after the White House was burned, where the salacious story below was shared. I am sure their descendants will be interested. Descendants.

The Lost Image of the James and Dolley Madison

THOMAS JEFFERSON AND THE HEMINGS DESCENDANTS

THOMAS JEFFERSON AND THE HEMINGS DESCENDANTS

We recently visited Poplar Forest (to the right), Thomas Jefferson’s retreat near Lynchburg, VA.

I noticed many references to John Hemmings and his contributions to the building of the house. Knowing the story of Sally Hemings and Jefferson, I was curious how Sally and John Hemings were related.

Records show that by the 1790s, seven different enslaved families were represented at Poplar Forest. Jefferson encouraged common-law unions amongst the enslaved community and recorded the birth dates of each enslaved child born on the property. He also rewarded women who married a fellow slave from Poplar Forest with a pot; archaeologists have found remnants of these gifts in archaeological studies of the property. Jefferson kept records of family connections – surviving records have allowed scholars to conclude that multiple generations of single families were enslaved at Poplar Forest and had relatives at other plantations in Virginia.

John Hemmings was born into slavery at Monticello on April 24, 1776. He was the youngest son of the enslaved, mixed-race Betty Hemings, and his father was Joseph Neilson, an Irish workman and Jefferson’s chief carpenter at Monticello. Hemmings was the eleventh of Betty’s children and half-brother to her six children by her enslaver John Wayles (Jefferson’s father-in-law), including Sally Hemings, as well as to the oldest four by an unknown father. So, John and Sally were half-siblings.

Because of a 1655 Virginia House of Burgesses law that determined an individual’s enslaved or free status through the individual’s mother, John Hemings was enslaved despite his three-quarters European heritage.

Jefferson allowed the Hemings family members a greater amount of agency than was typical for the period: the men were allowed to travel by themselves, learn trades, and hire themselves out on free days and keep the extra wages.

At age 14, Hemmings worked as an “out-carpenter” in the woods and fields, chopping trees and building fences, barns, and three slave cabins on Mulberry Row at Monticello. At some point, Hemmings also learned how to read and write, although exactly when and who taught him is unclear; unlike the rest of his family, he spelled his name with a double m.

Hemmings trained in the Monticello Joinery and became a highly skilled carpenter and woodworker, making furniture and crafting the fine woodwork of the interiors at Monticello and Poplar Forest.

Hemmings also served as the master joiner to apprentices Beverley, Madison, and Eston Hemings, Jefferson’s sons by Sally Hemings.

After decades of service, John Hemmings was freed in 1826 by Jefferson’s will and given the tools to the joinery. He remained at Monticello until about 1831 and died in 1833.

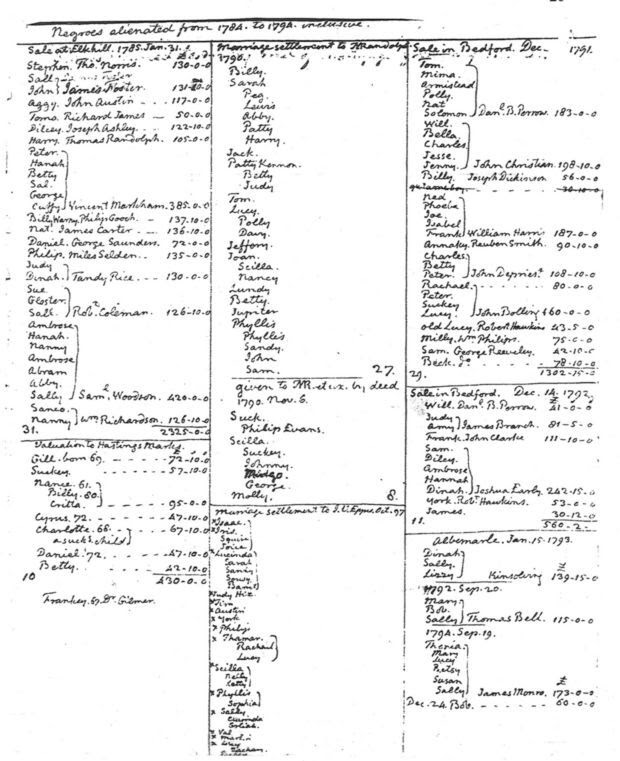

The document below is from Jefferson’s Farm Book titled “Negroes Alienated from 1784-1794, inclusive.” Jefferson used brackets to indicate family groups sold as a single lot. The name to the bracket’s right was the buyer and the enslaved family’s or individual’s new master. Descendants.

DESCENDANTS- BETWEEN THIS GUY AND BENEDICT ARNOLD, WE WERE FORTUNATE TO WIN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR

DESCENDANTS- BETWEEN THIS GUY AND BENEDICT ARNOLD, WE WERE FORTUNATE TO WIN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR

At the outbreak of the American Revolution, Charles Lee resigned his post in the British Royal Army to join the colonists in their patriotic cause. To Lee’s chagrin, George Washington surpassed the British-born officer as Congress’s choice for Commander of the Continental Army. Although Lee was widely recognized for his skillful military capabilities, after only a few years into the war, his reputation would be tarnished entirely.

Charles Lee was born in Cheshire, England, on January 26, 1731. As a boy, he was enrolled in military school and later served in the French and Indian War as a Lieutenant. While in America, Lee married a Mohawk woman and was adopted into the tribe. Due to Lee’s erratic temperament, the Native Americans called him “Boiling Water.”

In 1773, Lee returned to the colonies to establish a more permanent residence in Virginia. When hostilities between Britain and the American colonies erupted in 1775, all hope for reconciliation was extinguished, and the two sides plunged into war. As second in command of the Continental Army, Lee was appointed head of the Southern Department. However, his resentment for Washington as Commander-in-Chief would continue to surface throughout the war.

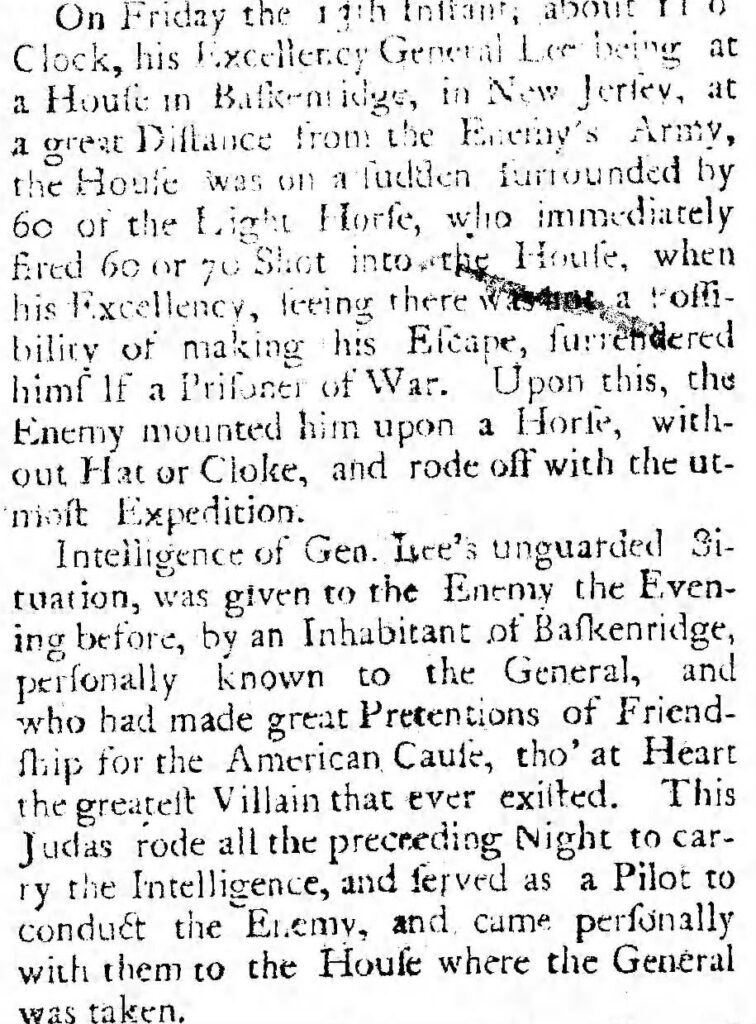

The Major General garnered substantial praise and admiration for his defense of Charleston in 1776. Though the judgment of others largely accomplished the victory, Lee was credited with the win and dubbed a hero. In the following months, Lee joined Washington in New York, where the “hero of Charleston” began badmouthing his superior in written correspondences. Longing for Washington’s job and exploiting the colonists’ recent defeats in New York, Lee penned a Congressman, “Had I the powers, I could do you much good.” The Major’s efforts to undermine General Washington were disrupted when, on December 12, 1776, Lee was captured by British troops at White’s Tavern in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, while writing a letter to General Horatio Gates complaining about Washington’s deficiency.

As second in command, Lee was a notable prize for the enemy, and his release would only come in 1778 after a British loss at Saratoga.

In May of 1778, Lee returned to the Continental Army in time for the Battle of Monmouth. The decisive battle occurred on June 28 as the Patriots pursued the British into New Jersey. Lee was ordered to lead the troops into battle, but what followed proved disastrous for the general. As the British began to flank Lee’s men, the commander prematurely issued a retreat. Witnessing this, Washington confronted Lee on the battlefield, and the two commanders exchanged heated words. Charged with disobeying orders and insubordination, Lee was relieved of his command and court-martialed. Congress decided to remove Lee for one year, during which time the ex-general spoke out against Washington.

Indeed, Lee’s sharp tongue created new enemies determined to defend Washington’s honor. In 1778, John Laurens challenged Lee to a duel and shot him in the side, wounding but not killing the officer. In 1780, Lee formally resigned from the Continental Army and retired to his Prato Rio property, where he bred horses and dogs. However, debts had again accumulated, and his advisors recommended liquidating the property. By the spring of 1780, in addition to more frequent gout attacks, Lee had acquired a chronic cough, which, with other symptoms, might have indicated tuberculosis. He made a final tour of Baltimore, Williamsburg, and Fredericksburg, Virginia; Frederick, Maryland; and western Pennsylvania. While visiting Philadelphia to complete the property’s sale, he was stricken with fever and died in an inn on October 2, 1782.

Lee’s place in history was further tarnished in the 1850s when George H. Moore, the librarian at the New York Historical Society, discovered a manuscript dated March 29, 1777, written by Lee while he was a British prisoner of war. It was addressed to the “Royal Commissioners”, i.e., Richard Howe, later 1st Earl Howe, and Richard’s brother, Sir William Howe, later 5th Viscount Howe, respectively, the British naval and army commanders in North America. It detailed a plan by which the British might defeat the rebellion. Moore’s discovery, presented in a paper titled “The Treason of Charles Lee” in 1858, influenced perceptions of Lee for decades. Descendants.

A REVOLUTIONARY ERA FEMINIST

A REVOLUTIONARY ERA FEMINIST

We visited the Lee Family home in Stratford, Virginia, near Washington’s birthplace. We learned about Hannah Ludwell Lee (pictured), born on February 6, 1728, on her parents’ Stratford Hall plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia. Her father was prominent civil servant Thomas Lee, and her mother was colonial heiress Hannah Ludwell. The fourth of eleven children, her siblings included Philip Ludwell, Francis Lightfoot, and Richard Henry, who signed the United States Declaration of Independence; Thomas Ludwell; diplomat Arthur; Alderman; William; and Alice. In 1747, Hannah Lee married her cousin Gawain Corbin (more below), who had succeeded his father as burgess but died in 1760 from injuries sustained in a horse-riding mishap; they had one daughter, Martha.

Following her husband’s death, Corbin inherited vast swathes of property, including 500 acres in Lancaster County and 2,250 acres in Caroline County, and slaves. She subsequently cohabited with Dr. Richard Lingan Hall, a widower who was the family physician for both the Lee and Corbin families and an early Baptist. The arrangement greatly displeased Hannah’s youngest brother, Arthur, and presumably others in the family and community. In 1763, Hannah gave birth to a son, Elisha, and a daughter, Martha. She gave them the Corbin surname so as not to violate her husband’s will, which stipulated that her inheritance would be forfeited if she remarried.

Reputedly, Richard Henry Lee was exasperated by Hannah’s refusal to settle Corbin’s estate, insisting that all that was necessary was that she sells “one middling slave”.

The following year, the Westmoreland County Court charged Dr. Hall and Hannah with failing to attend Anglican services. Corbin became a Baptist church member around 1764, to the disapproval of her siblings.

In March 1778, Corbin wrote to her brother Richard Henry, complaining about the “male domination in law and politics” while arguing for women’s suffrage: “Why should widows pay taxes when they have no voice in making the laws or in choosing the men who made them?” In response, he asserted that women were “already possessed of that right”. According to The Virginia Baptist Register, Corbin was the “first Virginia woman to take a stand for women’s rights”. Her descendants would be proud. Descendants.

THE LAST CIVIL WAR PENSION TO A CIVIL WAR DESCENDANT WAS PAID IN 2020

THE LAST CIVIL WAR PENSION TO A CIVIL WAR DESCENDANT WAS PAID IN 2020

My son-in-law’s 4 times Great Grandfather Stephen Danley at age 41, enlisted on August 11, 1864, in Grafton, WV, as a private in Co. B. 17th WV Infantry, Union Army. According to his pension papers, he was absent without leave for eleven days beginning December 20, 1864. Sounds like he went home for Christmas. He was discharged on June 30, 1865.

His wife Sarah died before the end of the Civil War. After Sarah’s death, Stephen, at age 45, married 26-year-old Roanna H. Gough/Goff on May 31, 1865, in Gilmer, WV after Sarah’s death. Roanna was the daughter of Joshua Holland Gough and Cassandra Jane “Cassie” Mc Donald Gough Snider and stepdaughter of Levi Snider.

Stephen was discharged from the military on June 30, 1865, in Parkersburg, WV. Roanna supported them by providing housecleaning and laundry services for others.

Stephen died on March 15, 1869, in the house of Roanna’s stepfather Levi Snider, in Parkersburg, Wood, WV, at 50, of chronic dyspepsia and tuberculosis.

Levi Snider was appointed the guardian of Stephen and Roanna’s minor child, Elizabeth. Levi filed a pension claim on September 17, 1873, applying for military pension benefits for Elizabeth. The government stated that there was no evidence that Stephen got tuberculosis from his service, even though at the time of his discharge, he complained of pain in his chest and lungs. The physician who examined him had moved away and possibly died. Also, there was no proof of his death.

In addition, a neighbor, Benjamina Cox, said that he left her a few days after Stephen married Roanna. About a year after the marriage, she told Benjamina that Stephen was not Elizabeth’s father. She said other women in the neighborhood would swear to the same.

T.M. Brannan, said that Roanna “was one of those loose women who had several children before she married and continued to have children after his death.” It was restated that she “did not bear a good reputation for virtue and chastity.” Benjamina was the wife of Philip Cox, who ironically was paid $25 to represent the interests of Roanna Danley as her pension agent. I did find evidence of a child out of wedlock before her marriage to Stephen and one afterward.

Several others, who were well acquainted, swore that Elizabeth was their child and that Stephen had acknowledged so. A couple of those ladies were the “other women in the neighborhood” referred to by Benjamina. Some of the witnesses were half-siblings of Elizabeth. A military official noted in the massive file that “the widow’s character before her and during marriage to the soldier is not a subject of inquiry in this case, as we have nothing to do with her reputation before or after the soldier’s death.”

Roanna died on September 28, 1877, in WV, at 39.

The claim was rejected 19 years later, on November 25, 1892, due to the inability to prove that the soldier acquired the disease while in the army. The government acknowledged that processing a claim should never have taken this long.

Elizabeth appealed the case on April 11, 1894. Another witness came forth and said that Stephen was thrown from a boat while crossing the Holly River in Braxton County, WV, in mid-January 1865 into the water, which is how he contracted the cold and cough and had his feet frozen on a scouting trip in the Elk and Holly River Valleys, and had developed a violent cold.

I never saw evidence of anyone being paid a pension, and the issue likely ended when Elizabeth died on October 20, 1895.

Here’s a more recent case:

“One beneficiary from the Civil War [is] still alive and receiving benefits,” Randy Noller of the Department of Veterans Affairs confirms.

Irene Triplett – the 86-year-old daughter of a Civil War veteran – collects $73.13 each month from her father’s military pension. The identity of Triplett was first reported by The Wall Street Journal in 2014.

“VA is obliged to care for our nation’s veterans no matter how long. It is an honor to serve and care for those who served our country,” Noller explained in an email to U.S. News.

Triplett’s father was Mose Triplett (pictured above middle), born in 1846. He joined the Confederate army in 1862 but later deserted and signed up with the Union. His first wife died, and they did not have any children. He later married Elida Hall, who was at least 50 years younger. They had five children, three of whom did not survive infancy. But Irene and her younger brother Everette did. Mose Triplett was 83 when Irene was born and nearly 87 when her brother Everette came along.

Mose Triplett died a few days after returning from the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1938. His wife and daughter went to live in public housing, and his son ran away. Elida Triplett died in 1967. Everette Triplett died in 1996.”

Irene Triplett died in 1920. Descendants.

WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS?

WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS?

Reach out to Dancestors Genealogy. Our genealogists will research, discover, and preserve your family history. No one is getting any younger, and stories disappear from memory every year and eventually from our potential ability to find them.

Preserve your legacy, and the heritage of your ancestors.

Paper gets thrown in the trash; books survive!

So please do not hesitate and call me @ 214-914-3598 and get your project started!

COULD YOU GET A PENSION FOR YOUR DESCENDANTS IF YOU HAD A JOB WITH NO SALARY?

COULD YOU GET A PENSION FOR YOUR DESCENDANTS IF YOU HAD A JOB WITH NO SALARY? AARON BURR PLAYING CUPID

AARON BURR PLAYING CUPID THOMAS JEFFERSON AND THE HEMINGS DESCENDANTS

THOMAS JEFFERSON AND THE HEMINGS DESCENDANTS DESCENDANTS- BETWEEN THIS GUY AND BENEDICT ARNOLD, WE WERE FORTUNATE TO WIN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR

DESCENDANTS- BETWEEN THIS GUY AND BENEDICT ARNOLD, WE WERE FORTUNATE TO WIN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR A REVOLUTIONARY ERA FEMINIST

A REVOLUTIONARY ERA FEMINIST THE LAST CIVIL WAR PENSION TO A CIVIL WAR DESCENDANT WAS PAID IN 2020

THE LAST CIVIL WAR PENSION TO A CIVIL WAR DESCENDANT WAS PAID IN 2020 WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS?

WHAT ABOUT YOUR DESCENDANTS?