27 Aug Genealogist- Newsletter- August 26, 2023

Contents

- 1 GENEALOGIST- HENRY ALEXANDER CLIMBED THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN THE U.K IN A CAR

- 2 GENEALOGIST- FLORA MACDONALD’S HEADSTONE ON THE ISLE OF SKYE

- 3 GENEALOGIST- TAKE YOUR CHILDREN TO WORK TODAY

- 4 GENEALOGIST- CONTINUING WITH SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OR THE CONSTITUTION

- 5 GENEALOGIST- ANOTHER NELSON STATUE

- 6 GENEALOGIST- WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

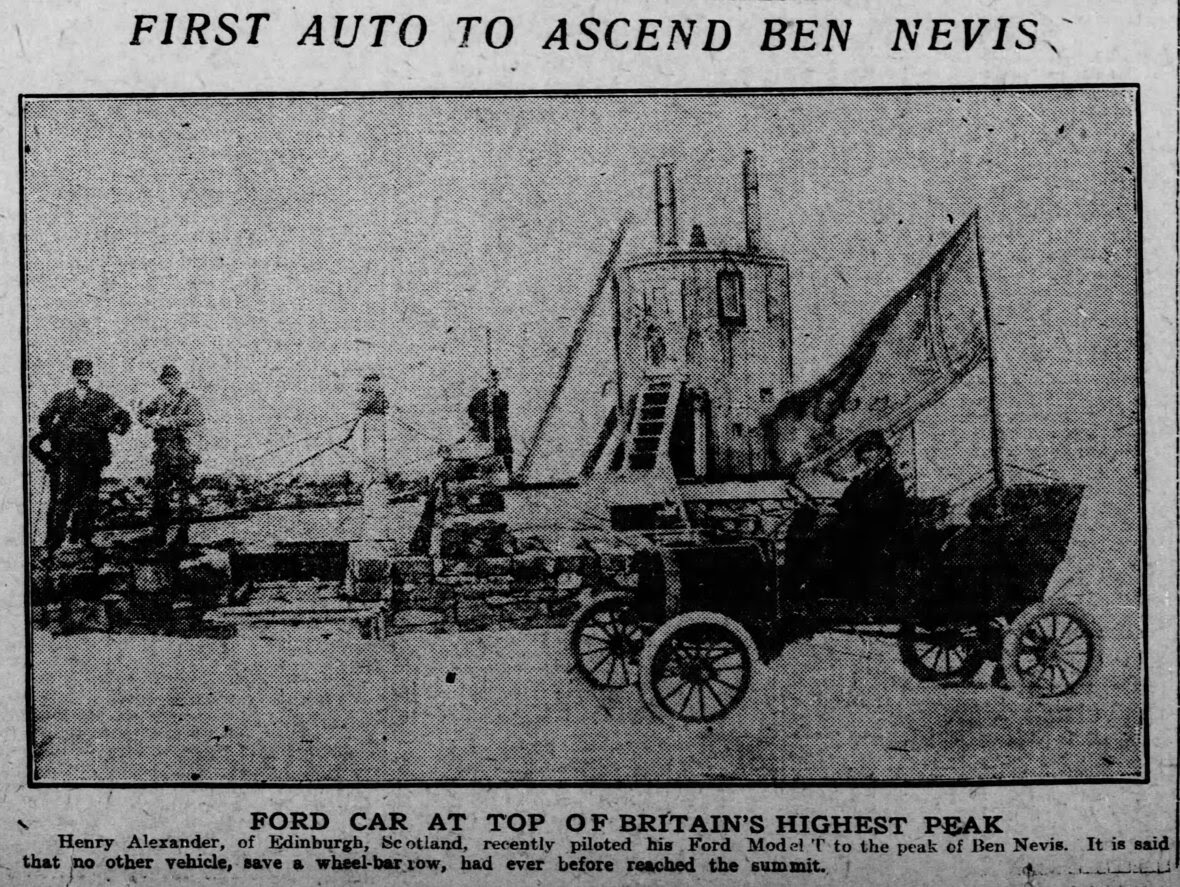

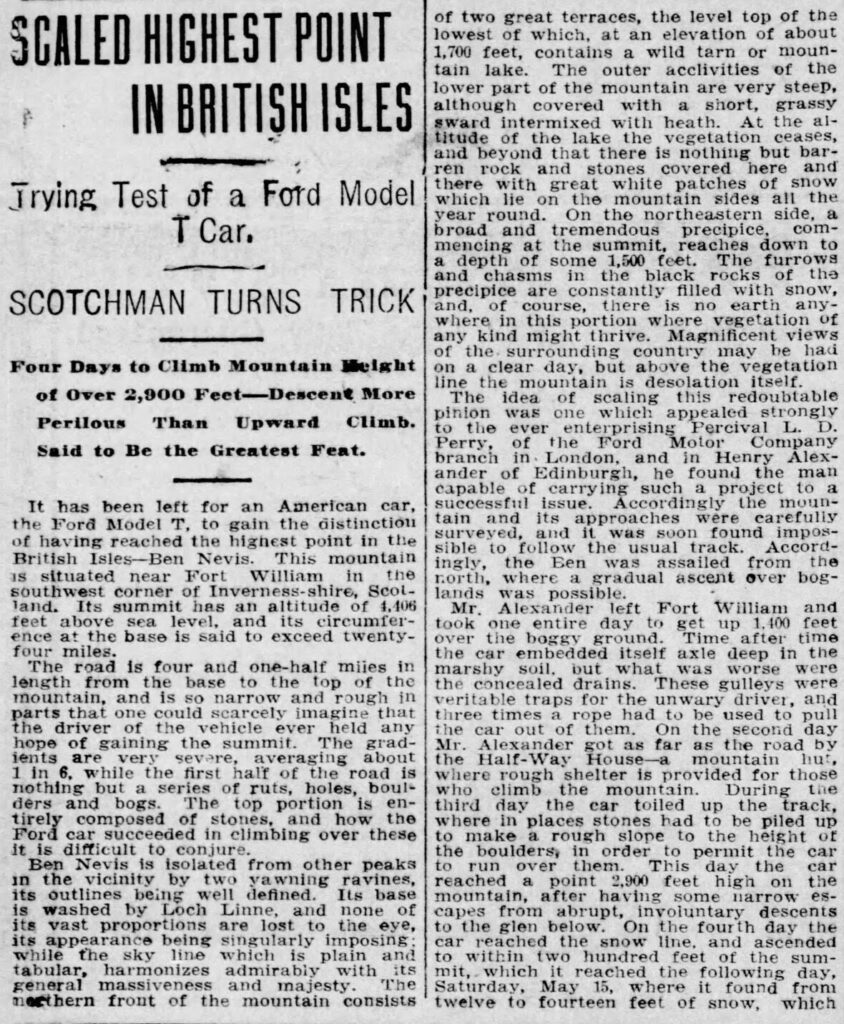

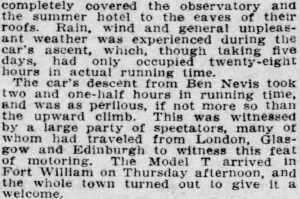

GENEALOGIST- HENRY ALEXANDER CLIMBED THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN THE U.K IN A CAR

GENEALOGIST- HENRY ALEXANDER CLIMBED THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN THE U.K IN A CAR

They commemorated a statue in Fort William in 2018. Here’s the article from 1911 ascent.

GENEALOGIST- FLORA MACDONALD’S HEADSTONE ON THE ISLE OF SKYE

GENEALOGIST- FLORA MACDONALD’S HEADSTONE ON THE ISLE OF SKYE

Flora MacDonald (1722 – 5 March 1790) was a member of Clan Macdonald of Sleat. MacDonald was visiting Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides when Prince Charles and a small group of aides took refuge there after the Battle of Culloden in June 1746. One of his companions, Captain Conn O’Neill from County Antrim, was distantly related to MacDonald and asked for her help. MacDonald of Sleat had not joined the Rebellion and Benbecula was controlled by a pro-government militia commanded by MacDonald’s step-father, Hugh MacDonald. This connection allowed her to obtain the necessary permits but she apparently hesitated, fearing the consequences for her family if they were caught. She may have been taking less of a risk than it appears; witnesses later claimed Hugh advised the Prince where to hide from his search parties.

Passes were issued allowing passage to the mainland for MacDonald, a boat’s crew of six men and two personal servants, including Charles disguised as an Irish maid called Betty Burke. On 27 June, they landed near Sir Alexander’s house at Monkstadt, near Kilbride, Skye. In his absence, his wife Lady Margaret arranged lodging with her steward, MacDonald of Kingsburgh, who told Charles to remove his disguise, as it simply made him more conspicuous. The next day, Charles was taken from Portree to the island of Raasay; MacDonald remained on Skye and they never met again.

Two weeks later, the boatmen were detained and confessed; MacDonald and Kingsburgh were arrested and taken to the Tower of London. After Lady Margaret interceded on her behalf with the chief Scottish legal officer, Duncan Forbes of Culloden, she was allowed to live outside the Tower under the supervision of a “King’s Messenger” and released after the June 1747 Act of Indemnity. Aristocratic sympathisers collected over £1,500 for her, one of the contributors being Frederick, Prince of Wales, heir to the throne; she allegedly told him she helped Charles out of charity and would have done the same for him.

On 6 November 1750, at the age of 28, she married Allan MacDonald, a captain in the British Army and Kingsburgh’s eldest son.[7] The couple first lived at Flodigarry on Skye.

During the 1756–1763 Seven Years’ War, Allan MacDonald had served with some distinction in the 114th and 62nd Regiments of Foot.

After his return to Scotland, Allan and Flora MacDonald were visited at Flodigarry in 1766 by North Uist poet John MacCodrum, an iconic figure in Scottish Gaelic literature. Fully aware of MacCodrum’s infamy as a satirist, Allan and Flora lavished hospitality upon the Bard as soon as he was recognized and, in return, MacCodrum composed a work of praise poetry beginning, God has given you a choice mate”).

Allan and Flora inherited the tack of Kingsburgh in 1772, after her father in law died. The poet, essayist, and lexicographer Samuel Johnson met her in 1773 during his visit to the island, and later described her as “a woman of soft features, gentle manners, kind soul and elegant presence”. He was also author of the inscription on her memorial at Kilmuir: “a name that will be mentioned in history, and if courage and fidelity be virtues, mentioned with honour”.

Allan MacDonald, however, proved to be a poor land agent and an even poorer businessman. After quarrelling with his landlord over debts and rent, he and Flora emigrated in 1774 to Anson County, North Carolina, and settled with other Clan Donald transplants on a plantation they named “Killegray”, near Mount Pleasant, which is now Cameron Hill, North Carolina. When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, Allan raised the Anson Battalion of the Loyalist North Carolina Militia, a total of around 1,000 men, including their sons Alexander and James.

Tradition records that as the Anson battalion assembled in Cross Creek on 15 February 1776, Flora “addressed them in their own Gaelic tongue and excited them to the highest pitch of warlike enthusiasm”, a tradition known among the Scottish clans as a “brosnachadh-catha” or “incitement to battle.” They then set off for the coast to link up with some 2,000 British reinforcements commanded by General Henry Clinton, who in reality had only just sailed from Cork in Ireland. Early on the morning of 17 February, they were ambushed at Moore’s Creek Bridge by Patriot militia led by Richard Caswell and along with his troops, Allan MacDonald was taken prisoner.

After the battle, Flora was interrogated by North Carolina’s Committee of Safety, before which she exhibited “spirited behavior.” In April 1777, all Loyalist-owned property was confiscated by the North Carolina Provincial Congress and Flora was evicted from Killegray, with the loss of all her possessions. After 18 months in captivity, Allan was released as part of a prisoner exchange in September 1777 and posted to Fort Edward, Nova Scotia as commander of the 84th Regiment of Foot. Here he was joined by Flora in August 1778.

After a harsh winter in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in September 1779 MacDonald took passage for London in the Dunmore, a British privateer; during the voyage, she broke her arm and ill-health delayed her return to Scotland until spring 1780. She spent the next few years living with various family members, including Dunvegan home of her son-in-law Major General Alexander MacLeod, the largest landowner in Skye after the MacDonalds. The compensation received for the loss of their property in North Carolina was insufficient to allow them to resettle in Nova Scotia and Allan returned to Scotland in 1784. Kingsburgh was now occupied by Flora’s half-sister and her husband, and Allan instead took up tenant farming in nearby Penduin.

According to American historian John Patterson MacLean, Flora often said in later life that she first served the House of Stuart and then the House of Hanover and was worsted in the cause of each. She died in 1790 at the age of 68 and was buried in Kilmuir Cemetery, followed by her husband in September 1792. They had seven surviving children, two daughters and five sons, two of whom were lost at sea in 1781 and 1782; a third son John made his fortune in India, enabling his parents to spend their last years in some comfort.

GENEALOGIST- TAKE YOUR CHILDREN TO WORK TODAY

GENEALOGIST- TAKE YOUR CHILDREN TO WORK TODAY

We saw this recreation at the Royal Scots Regimental Museum.

Take a closer look at the knapsack on McBain’s back. A plaque explains that his wife had decided to return to Scotland from the regiment’s winter quarters and handed over their baby while McBain was still on parade. “Having nowhere else to put him, Private McBain fought the battle with the child in his knapsack.”

GENEALOGIST- CONTINUING WITH SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OR THE CONSTITUTION

GENEALOGIST- CONTINUING WITH SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OR THE CONSTITUTION

John Witherspoon (February 5, 1723 – November 15, 1794) was a Scottish-American Presbyterian minister, educator, farmer, slaveholder, and a Founding Father of the United States. Witherspoon embraced the concepts of Scottish common sense realism, and while president of the College of New Jersey (1768–1794; now Princeton University) became an influential figure in the development of the United States’ national character. Politically active, Witherspoon was a delegate from New Jersey to the Second Continental Congress and a signatory to the July 4, 1776, Declaration of Independence. He was the only active clergyman and the only college president to sign the Declaration. Later, he signed the Articles of Confederation and supported ratification of the Constitution of the United States.

Witherspoon was a staunch Protestant, nationalist, and supporter of republicanism. Consequently, he was opposed to the Roman Catholic Legitimist Jacobite rising of 1745–46. Following the Jacobite victory at the Battle of Falkirk, he was briefly imprisoned at Doune Castle (which we visited earlier this week), which had a long-term effect on his health.

At the urging of Benjamin Rush and Richard Stockton, whom he met in Paisley, Witherspoon finally accepted their renewed invitation (having turned one down in 1766) to become president and head professor at the small Presbyterian College of New Jersey in Princeton. Thus, Witherspoon and his family emigrated to New Jersey in 1768.

At the age of 45, he became the sixth president of the college, later known as Princeton University. Upon his arrival, Witherspoon found the school in debt, with weak instruction, and a library collection which clearly failed to meet student needs. He immediately began fund-raising—locally and back home in Scotland—added three hundred of his own books to the library, and began purchasing scientific equipment including the Rittenhouse orrery, many maps, and a terrestrial globe. Witherspoon instituted numerous reforms, including modeling the syllabus and university structure after that used at the University of Edinburgh and other Scottish universities. He also firmed up entrance requirements, which helped the school compete with Harvard and Yale for scholars.

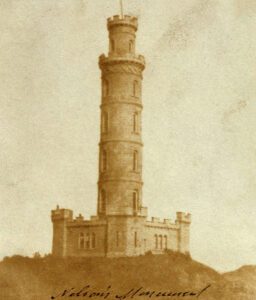

GENEALOGIST- ANOTHER NELSON STATUE

GENEALOGIST- ANOTHER NELSON STATUE

You can’t go far in the U.K. without coming across a namesake Nelson statue.

The link below ties to a March 2022 article about the Nelson statue in London, and the former statue in Dublin. We hiked up to this monument standing over Edinburgh.

The Nelson Monument is a commemorative tower in honor of Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, located in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is situated on top of Calton Hill, and provides a dramatic termination to the vista along Princes Street from the west. The monument was built between 1807 and 1816 to commemorate Nelson’s victory over the French and Spanish fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, and his own death at the same battle. In 1852 a mechanized time ball was added, as a time signal to shipping in Leith harbour. The time ball is synchronized with the One O’Clock Gun firing from Edinburgh Castle. The monument was restored in 2009.

The Royal Navy’s White Ensign and signal flags spelling out Nelson’s famous message “England expects that every man will do his duty” are flown from the monument on Trafalgar Day each year.

GENEALOGIST- WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

GENEALOGIST- WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

Reach out to Dancestors to research, discover, and preserve your family history. No one is getting any younger, and stories disappear from memory every year and eventually from our potential ability to find them. Paper gets thrown in the trash; books survive! So do not hesitate and call your genealogist @ 214-914-3598.

GENEALOGIST- HENRY ALEXANDER CLIMBED THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN THE U.K IN A CAR

GENEALOGIST- HENRY ALEXANDER CLIMBED THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN THE U.K IN A CAR GENEALOGIST- FLORA MACDONALD’S HEADSTONE ON THE ISLE OF SKYE

GENEALOGIST- FLORA MACDONALD’S HEADSTONE ON THE ISLE OF SKYE GENEALOGIST- TAKE YOUR CHILDREN TO WORK TODAY

GENEALOGIST- TAKE YOUR CHILDREN TO WORK TODAY GENEALOGIST- CONTINUING WITH SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OR THE CONSTITUTION

GENEALOGIST- CONTINUING WITH SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OR THE CONSTITUTION GENEALOGIST- ANOTHER NELSON STATUE

GENEALOGIST- ANOTHER NELSON STATUE GENEALOGIST- WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?

GENEALOGIST- WHAT ABOUT YOUR ANCESTORS?