08 Jul LEGACY- Newsletter- July 15, 2023

Contents

- 1 LEGACY- JEWISH REFUGEES IN SHANGHAI

- 2 LEGACY- A LETTER FROM BILL

- 3 LEGACY- SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE, THAT MOST PEOPLE HAVE NOT HEARD OF…

- 4 LEGACY- AND YOU THOUGHT POLITICS OVER THANKSGIVING DINNER WERE HARD AT YOUR HOUSE.

- 5 LEGACY- WITH THE TEXAS RANGERS HAVING A GOOD SEASON AND VISITING THE GEORGE W. BUSH LIBRARY. I WAS REMINDED OF HIS LOVE OF BASEBALL AND ANOTHER BUSH STORY

- 6 LEGACY- SO YOU MET YOUR SPOUSE AT THE FAMILY PICNIC?

- 7 LEGACY- BOMBS AWAY. TARGET MISSED

- 8 LEGACY- WERE YOUR ANCESTORS INTO ROCK AND ROLL?

LEGACY- JEWISH REFUGEES IN SHANGHAI

LEGACY- JEWISH REFUGEES IN SHANGHAI

One of our clients shared a story about her husband’s ancestors fleeing Nazi Germany by going to Shanghai. She had a small book listing all of the refugees. I had to look up that story.

An estimated 17,000 German and Austrian Jews first trickled into Shanghai after the beginning of Nazi persecution of Jews in 1933, and then, following the 1938 violence of Kristallnacht streamed in like a flood. These early refugees usually immigrated to Shanghai as families. Stripped of most of their assets before fleeing the Reich, these thousands of refugees swarmed into Hongkew because they could not afford to live anywhere else in the foreign concessions.

During the 1930s, Nazi policy encouraged Jewish emigration from Germany, and a ship’s passage enabled a person to gain release, even from a concentration camp. At first, Shanghai seemed an unlikely refuge, but as it became clear that most countries were limiting or denying entry to Jews, it became the only available choice. Until August 1939, no visas were required to enter Shanghai.

Arrival in Shanghai was a shock, especially for those who had just stepped off a European liner on which uniformed stewards had served breakfast and found themselves lining up for lunch in a soup kitchen. Finding work was a challenge once the refugees settled in, and many refugees had to rely on at least some charitable relief.

Still, the majority of German and Austrian Jews managed. Despite the blows to Shanghai’s economy dealt by the Sino-Japanese conflict, some adapted well, taking advantage of the city’s opportunities. The Eisfelder family, who arrived at the end of 1938, opened and operated Café Louis, a popular gathering place for refugees throughout the war years. Others established small factories or cottage industries, set themselves up as doctors or teachers, or worked as architects or builders to transform sections of bombed-out Hongkew, and left their legacy. By 1940, an area around Chusan Road was known as “Little Vienna,” owing to its European-style cafés, delicatessens, nightclubs, shops, and bakeries.

When Shanghai’s refugee population suddenly jumped from about 1,500 at the end of 1938 to nearly 17,000 one year later, the local Jews were overwhelmed and hard-pressed to find the resources to help needy families. The Committee for Assistance of European Jewish Refugees in Shanghai, formed in 1938 by prominent local Jews, turned to the Joint Distribution Committee in New York for additional funds. The JDC appropriation rose from $5,000 1938 to $100,000 in 1939. Even this barely kept up with the mounting demands. By late 1939, more than half of the refugee population required financial help for food or housing.

The Committee for Assistance established five group shelters for a minority of impoverished German and Austrian Jews. These shelters were called Heime (“homes” in German). The Ward Road Heim that opened in January 1939 was hastily converted from a former barracks and outfitted with hard, narrow bunk beds under which the residents stored their few belongings (see above). By the end of 1939, about 2,500 people lived in the Heime, sleeping anywhere from six to 150 a room. An additional 4,500 individuals ate in soup kitchens in the Heime but lived elsewhere in rented rooms. Many received relief help to pay for all or part of their housing costs.

LEGACY- A LETTER FROM BILL

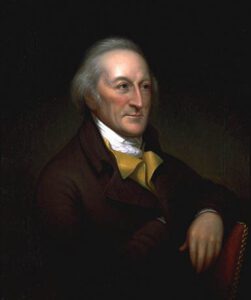

LEGACY- SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE, THAT MOST PEOPLE HAVE NOT HEARD OF…

LEGACY- SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE, THAT MOST PEOPLE HAVE NOT HEARD OF…

George Clymer (March 16, 1739 – January 23, 1813) was an American politician, abolitionist, and Founding Father of the United States, one of only six founders who signed the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Clymer was among the earliest patriots to advocate for complete independence from Britain. He attended the Continental Congress and served in political office until the end of his life. He was a Framer of the Constitution, where he attempted unsuccessfully to regulate the importation of slaves. Clymer was a minor slave owner, briefly through inheritance, when he was seven.

Clymer was born in Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania, on March 16, 1739. He was orphaned when only a year old; he was apprenticed to his maternal aunt and uncle, Hannah and William Coleman, to prepare to become a merchant. He married Elizabeth Meredith on March 22, 1765. In a letter written by Clymer to the rector of Christ Church, the Reverend Richard Peters, Clymer states that he had previously fathered a child; neither the child’s nor mother’s name is mentioned. Clymer and his wife had nine children, four of whom died in infancy. His oldest surviving son, Henry (born 1767), married the Philadelphia socialite Mary Willing in 1794. John Meredith, Margaret, George, and Ann also survived to adulthood, though John Meredith was killed in the Whiskey Rebellion in 1787 at age 18.

Clymer was a patriot and leader in the demonstrations in Philadelphia resulting from the Tea Act and the Stamp Act. Clymer accepted the command as a leader of a volunteer corps belonging to General John Cadwalader’s brigade. In 1759, he was inducted as a member of the original American Philosophical Society. He became a Philadelphia Committee of Safety member in 1773 and was elected to the Continental Congress from 1776–1780. Clymer shared the responsibility of being treasurer of the Continental Congress with Michael Hillegas. He served on several committees during his first congressional term. He was sent with Sampson Mathews to inspect the northern army at Fort Ticonderoga on behalf of Congress in the fall of 1776. When Congress fled Philadelphia in the face of Sir Henry Clinton’s threatened occupation, Clymer stayed behind with George Walton and Robert Morris. Clymer’s business ventures during and after the war increased his wealth. In 1779 and 1780, Clymer and his son Meredith engaged in a lucrative trade with Saint Eustatius. Although not partial to the merchant business, Clymer continued the business with his father-in-law and brother-in-law until 1782.

He resigned from Congress in 1777 and, in 1780, was elected to a seat in the Pennsylvania Legislature. In 1782, he was sent on a tour of the southern states in a vain attempt to get the legislatures to pay up on subscriptions due to the central government. He was re-elected to the Pennsylvania legislature in 1784 and represented his state at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He was elected to the first U.S. Congress in 1789.

He was the first president of The Philadelphia Bank and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and vice-president of the Philadelphia Agricultural Society. When Congress passed a bill imposing a duty on spirits distilled in the United States in 1791, Clymer was placed as head of the excise department for the state of Pennsylvania. He was also one of the commissioners to negotiate a treaty with the Creek Indian confederacy at Colerain, Georgia, on June 29, 1796. He is considered the benefactor of Indiana Borough, as he donated the property for a county seat in Indiana County, Pennsylvania.

Clymer died on January 23, 1813. He was buried at the Friends Burying Ground in Trenton, New Jersey.

Clymer is known to have been a slave owner to what degree is uncertain, although it is understood his father, grandfather, and brother were minor slave owners. When his father Christopher died, George, then seven years old, inherited “a negro man named Ned”, who died soon after. Ned was probably the only remains of an inheritance given to Christopher from his father, Richard, George’s grandfather, who owned four slaves.

As a member of the Pennsylvania delegation during the framing of the Constitution, Clymer unsuccessfully opposed the slave trade. The question of the slave trade, i.e., the import of new slaves into the United States, was one of the most contentious issues for the framers. Clymer was on the committee to draft a Slave Trade Compromise to postpone the slave trade decision until 1808. Clymer supported an “export tax” (tariff), a way to tax slavery indirectly, which, like the slave trade question, was opposed by southern states. Nevertheless, the tariff was included as part of the compromise. His legacy exists in many places.

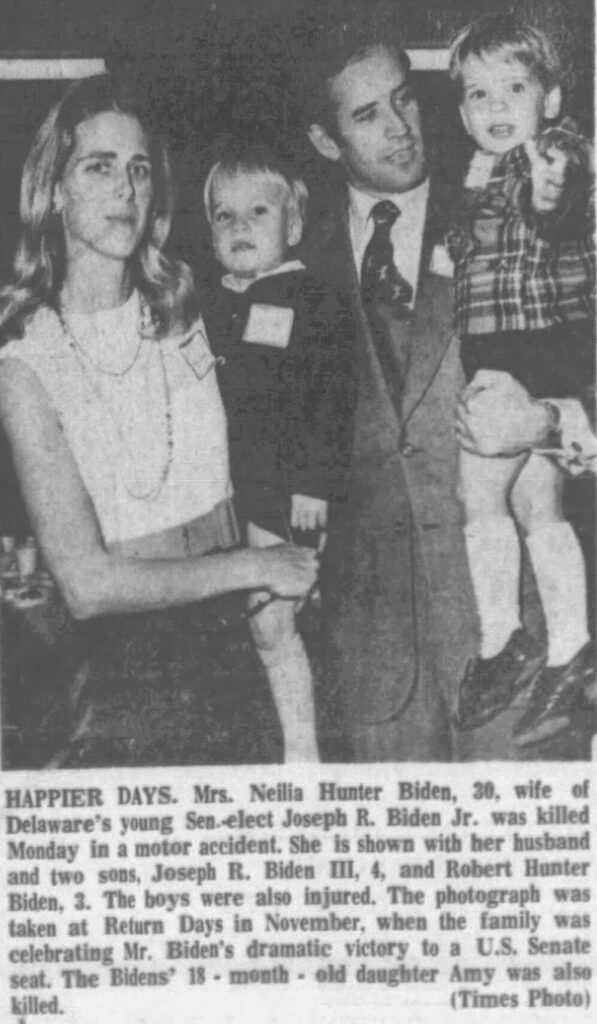

LEGACY- AND YOU THOUGHT POLITICS OVER THANKSGIVING DINNER WERE HARD AT YOUR HOUSE.

LEGACY- AND YOU THOUGHT POLITICS OVER THANKSGIVING DINNER WERE HARD AT YOUR HOUSE.

Frederick Fayette Dent was the father of Julia Dent Grant, father-in-law of Ulysses S. Grant, and the owner of the White Haven estate in St. Louis, Missouri, for more than forty years. Born on October 6, 1787, in Cumberland, Maryland, Dent grew up in a wealthy family that owned several slave plantations throughout Maryland. When his father died in 1802, Dent moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he became a trader and businessman. He specialized in the fur trade with various Indian tribes between St. Louis and Pittsburgh, including the Sauk and Meskwaki (Fox) tribes. Dent also served as a non-commissioned officer in the War of 1812 and fought in the Battle of Bladensburg.

After meeting his wife Ellen and starting a family, the Dents moved to St. Louis by 1819. Frederick Dent became a successful merchant and land speculator. The Dents originally rented a city home but soon accumulated enough money to purchase a second home twelve miles away in the St. Louis countryside the following year. Frederick Dent called this country home “White Haven,” after one of his family’s plantations in Maryland. As his wealth grew, Dent added land and purchased enslaved laborers to work the property. By 1830 White Haven was 850 acres and worked by eighteen enslaved African Americans (this number would increase to thirty by 1850). Signifying his desired status as a Southern gentleman, Dent referred to himself as “Colonel,” although he never held this rank during the War of 1812.

Frederick Dent’s status as a wealthy slaveholder influenced his political views. He strongly supported President Andrew Jackson and was friends with William Clark and Thomas Hart Benton, two of Missouri’s most popular pro-slavery politicians. He also served on the finance committee of the St. Louis Anti-Abolitionist Society. This organization was formed in 1846 to convince the Missouri State Legislature to pass stronger laws protecting the state’s slaveholders’ rights. Dent was known within the family circle for avidly reading newspapers and discussing politics in the White Haven dining room. When Ulysses S. Grant lived at White Haven from 1854 to 1859, the two regularly discussed slavery and the possibility of civil war in the United States.

About a month after the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861, Grant came to visit Colonel Dent at White Haven while mustering troops in nearby Belleville, Illinois. Ulysses reported to Julia that her father supported the Union but opposed any efforts by the federal government to prevent a southern state from joining the Confederacy. “Your father . . . is really what I would call a secessionist,” according to Grant. As the Civil War continued, Colonel Dent refused to take a loyalty oath and argued to Julia that secession was constitutional.

Frederick Dent was financially ruined by the end of the Civil War. The remaining enslaved laborers ran away from White Haven in 1864, and past debts caught up to him. A stroke shortly after the war also affected his health. By 1866 Colonel Dent moved to Washington, D.C. When his now-famous son-in-law took the oath of office to become the 18th President of the United States in 1869, Dent moved into the White House with the Grants to live out his remaining years.

The Colonel didn’t hesitate to make himself at home. When his daughter received guests, he sat in a chair just behind her, offering anyone within earshot unsolicited advice. Political and business figures got a dose of the Colonel’s mind as they waited to meet President Grant.

When the president’s father, Jesse Grant, came from Kentucky on one of his regular visits to Washington, the White House became a Civil War reenactment.

According to “First Families: The Impact of the White House on Their Lives” by Bonnie Angelo, Jesse Grant preferred to stay in a hotel rather than sleep under the same roof as the Colonel.

And when the two old partisans found themselves unavoidably sitting around the same table in the White House, they avoided direct negotiations by using Julia and her young son, named for the president’s father, as intermediaries, Betty Boyd Caroli writes in “First Ladies”: “In the presence of the elder Grant, Frederick Dent would instruct Julia to ‘take better care of that old gentleman [Jesse Grant]. He is feeble and deaf as a post and yet you permit him to wander all over Washington alone.’ And Grant replied [to his grandson and namesake], ‘Did you hear him? I hope I shall not live to become as old and infirm as your Grandfather Dent.'”

The Colonel remained in the White House — irascible and unrepentant — until his death, at age 86, in 1873. He left quite a legacy.

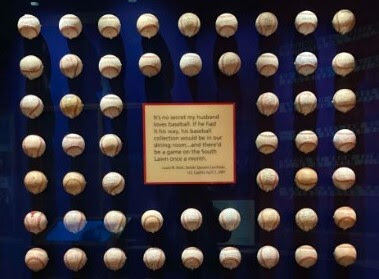

LEGACY- WITH THE TEXAS RANGERS HAVING A GOOD SEASON AND VISITING THE GEORGE W. BUSH LIBRARY. I WAS REMINDED OF HIS LOVE OF BASEBALL AND ANOTHER BUSH STORY

There is a picture of his signed baseball collection below.

My wife’s cousin told us the story from the mid to late 1950’s when they hosted a foreign exchange student from Cameroon. The students traveled across the U.S. and one of the stops was Midland, TX.

She often wonders if that boy from Cameroon ever realized that two of the people he stayed with later became Presidents of the United States. A interesting story of the Bush legacy.

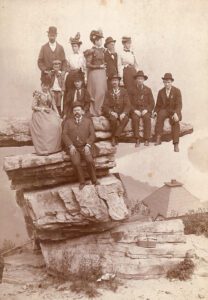

LEGACY- SO YOU MET YOUR SPOUSE AT THE FAMILY PICNIC?

While driving across America, we notice the signs for picnic areas, but with no one picnicking. All offramps leading to convenient, fast food appear to have supplanted the tradition. We may get to the cemetery faster if we eat enough fast food. Did you know that our ancestors needed a picnic spot, that the local cemetery was often the gathering spot?

Many people associate a cemetery exclusively with a place of sadness and sorrow. But in the United States, only a century and a half ago, real picnics were held in cemeteries. And here, young people got to know each other, relatives talked to each other and went to dinners arranged at family plots with the graves of the deceased.

This scenario would have seemed perfectly normal one hundred or so years ago. Cemeteries were prime picnic spots in the late 1800s. Remember, in the aftermath of the bloody Civil War and an age of cholera and yellow fever, cities created large new cemeteries to accommodate the dead. Family farms or sacred churchyards were no longer the only spots for burial grounds. These new-age cemeteries looked and functioned more like public parks than stark, spooky graveyards. They featured professional landscaping, winding paths, ponds, and pavilions.

In the 19th century, in the United States, people often gathered in cemeteries to relax and dine. One of the reasons for choosing such an exotic holiday destination was simple: at that time, in many municipalities, there were no proper holiday destinations, and the territory of cemeteries was always well-groomed and looked like modern parks amid numerous tombstones.

In Dayton (Ohio), women could decently wave their umbrellas, strolling between the graves on the way to their site in the Forest Cemetery. And in New York, residents slowly walked through the churchyard of St. Paul (Lower Manhattan), carrying baskets filled with all sorts of food in their hands.

The second reason for the appearance of the “fashion quirk” was sad: at that time, epidemics of various diseases were rampant in the country, there was a high infant mortality rate, and often women did not survive childbirth. Death was frequent in many families, and people could only calmly talk and have lunch with their family or friends at the cemetery. At the same time, they also “visited” the deceased relatives as part of an ongoing legacy.

Family members came to celebrate Thanksgiving with the deceased father or to bring gifts to the cemetery on Mother’s Day. They took sandwiches, snacks, and even spirit lamps to boil tea or coffee.

LEGACY- BOMBS AWAY. TARGET MISSED

LEGACY- BOMBS AWAY. TARGET MISSED

I recently read “The Bomber Mafia” by Malcolm Gladwell. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bomber_Mafia. In it, I learned about Carl Lucas Norden (April 23, 1880 – June 14, 1965), a Dutch American engineer who invented the Norden bombsight.

Norden was born in Semarang, Java. After attending a boarding school in Barneveld, Netherlands, he was educated at the ETH Zürich in Switzerland and emigrated to the United States in 1904.

Along with Elmer Sperry, Norden worked on the first gyrostabilizers for United States ships and became recognized for his contributions to military hardware. In 1913, he left Sperry to form his own company. In 1920, he began work on the Norden bombsight for the United States Navy. A prototype was available by 1923 (see above), and the first bombsight, containing an analog computer, was produced in 1927. Bombardiers were trained in great secrecy on how to use it. The device was used to drop bombs from high-altitude aircraft, accurately enough in practice to hit a 100-foot (30 m) circle from an altitude of 21,000 feet (6,400 m), but this accuracy was never achieved in combat.

Norden died in Zürich, Switzerland, on June 14, 1965. Norden was inducted into the US National Aviation Hall of Fame in July 1994. He left quite a legacy.

You must consider his work as a forerunner to our ability to deliver death via drone by almost tapping the intended on the shoulder first vs. destroying an entire city and thousands of people to take out a bad guy.

LEGACY- WERE YOUR ANCESTORS INTO ROCK AND ROLL?

LEGACY- WERE YOUR ANCESTORS INTO ROCK AND ROLL?

Reach out to Dancestors to research, discover, and preserve your family history. No one is getting any younger, and stories disappear from memory every year and eventually from our potential ability to find them. Paper gets thrown in the trash; books survive! So do not hesitate and call me @ 214-914-3598. Leave your legacy. See https://dancestorsgenealogy.com/ancestry-newsletter-july-1-2023/

LEGACY- JEWISH REFUGEES IN SHANGHAI

LEGACY- JEWISH REFUGEES IN SHANGHAI LEGACY- SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE, THAT MOST PEOPLE HAVE NOT HEARD OF…

LEGACY- SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE, THAT MOST PEOPLE HAVE NOT HEARD OF… LEGACY- AND YOU THOUGHT POLITICS OVER THANKSGIVING DINNER WERE HARD AT YOUR HOUSE.

LEGACY- AND YOU THOUGHT POLITICS OVER THANKSGIVING DINNER WERE HARD AT YOUR HOUSE. LEGACY- BOMBS AWAY. TARGET MISSED

LEGACY- BOMBS AWAY. TARGET MISSED LEGACY- WERE YOUR ANCESTORS INTO ROCK AND ROLL?

LEGACY- WERE YOUR ANCESTORS INTO ROCK AND ROLL?